This essay in this post is four years old, so first I should explain why I’m posting it now.

Later this month, a friend is getting married, and the ceremony is very near to the house I write about in the piece. Looking forward to the wedding prompted a look back at the essay, but when I searched online, I couldn’t find it. The site that published it has gone. That site was a blog run by a writer called Brian Hamill - the lovely soul behind The Common Breath, a Glasgow-based imprint committed to innovative writing. The blog was Brian’s way of getting new writers in front of readers. I’d met him on Twitter. When I submitted a piece about Scott Walker he was generous about my writing and in the effort he took setting the piece on the page. He invited me to submit again. In January 2021 he accepted this essay on Stefan Zweig.

Then, in May that year, Brian’s family reported him missing. CCTV captured him in the early hours of morning. Two weeks on, his body was found in the River Clyde. Someone who offered me a lifeline, in the darkest days of the pandemic, had been in dire need of one himself.

We exchanged only a handful of emails, but people who knew Brian confirmed my impression: he was a kind, thoughtful and talented man. Thinking of all this now, and re-reading David Keenan’s beautiful tribute, I flashed back to that strange, convulsive period. The plague year. The Common Breath summed up for me the flowering of community that happened then, the remote forms of connection. But Brian’s experience also stands for the isolation, the struggles, the collision with uncomfortable truths. Five years on, some positives from that time endure, but if anything we feel further down the wrong track. Stories of that time fade from view. So, sadly, do traces of Brian Hamill. The equivalent to the renewed artistic expression that Stefan Zweig witnessed in post-war Austria feels further away than ever. But Zweig’s writing, like Brian’s DIY ethos, continues to offer hope. Maybe, as I say in the essay, it’s (still) too soon to judge. Maybe tomorrow is where it’s at. Re-reading this essay after many years, I find myself thinking how important it is we stick around, and try to find out together.

Just as it was in the first place, this one’s for Brian.

The World Of Yesterday: Searching for Stefan Zweig

Bath Spa railway station nestles in the south east corner of the city centre, just inside the elbow of the River Avon.

As the river doubles back on itself and aligns with the echoing contours of the A36, a steep bank of hills climb up towards the Bath Skyline. The Skyline is the circular walk that overlooks the city, though ‘city’ seems too cute a description for the view from above. Bath’s Georgian marvel is a sophisticated cluster of sandcastles. The destructive waves of architecture that should have eroded it never arrived. Maybe the hills held them back.

The hills also hide the building I’m here to look at. The house of a writer. We’re here in the days before Christmas 2020, the whole family in need of The Outside and a view - perhaps of a ‘city’ like Bath. The dog is desperate for a walk. So are the children. But first I have to find the house.

As clues, I have a picture of the front gate and a name: Rosemount. It has the ring of another time, don’t you think, Rosemount, a time of mystery when the internet didn’t explain everything and when a single name could hold a nameless power and sustain a great work of art. Like Rosebud, or Manderley. And as we make our way up into the fog and whatever mysteries it may contain, we leave behind the glut of layered modernity of the city’s south east corner, with its river and its train station and its trunk roads all entwined around themselves, successive transport technologies superseding but never quite replacing each other. We climb.

It feels like heading into the past. We drive past a small parade of shops lining a cobbled street, then up a winding road to the landscaped gardens of Prior Park. Before we reach the more rural setting of Claverton Down, we take a right turn, then another, and find ourselves heading up a very old, very narrow street: Rosemount Lane. Top-heavy houses on one side, doddery trees the other. The car feels crowded in. We edge forward in first gear, tilted back in our seats at a 20 degree angle. It’s like the chain lift of a rollercoaster. The kids are hollering. The adults breathe in.

The road opens out into a rural crossroads. There on a huge gate pillar I see the name. It’s painted in an elegant font. Beneath it is the giveaway plaque.

This is the place.

Someone is in the first floor window - a home office most likely. Now I’m here, I wonder what I should do. I feel torn. Should I soak up the significance of my visit? Or avoid standing like an idiot in the rain, staring at someone’s white stone wall? I take a couple of obligatory photos. I stand there for a few more beats.

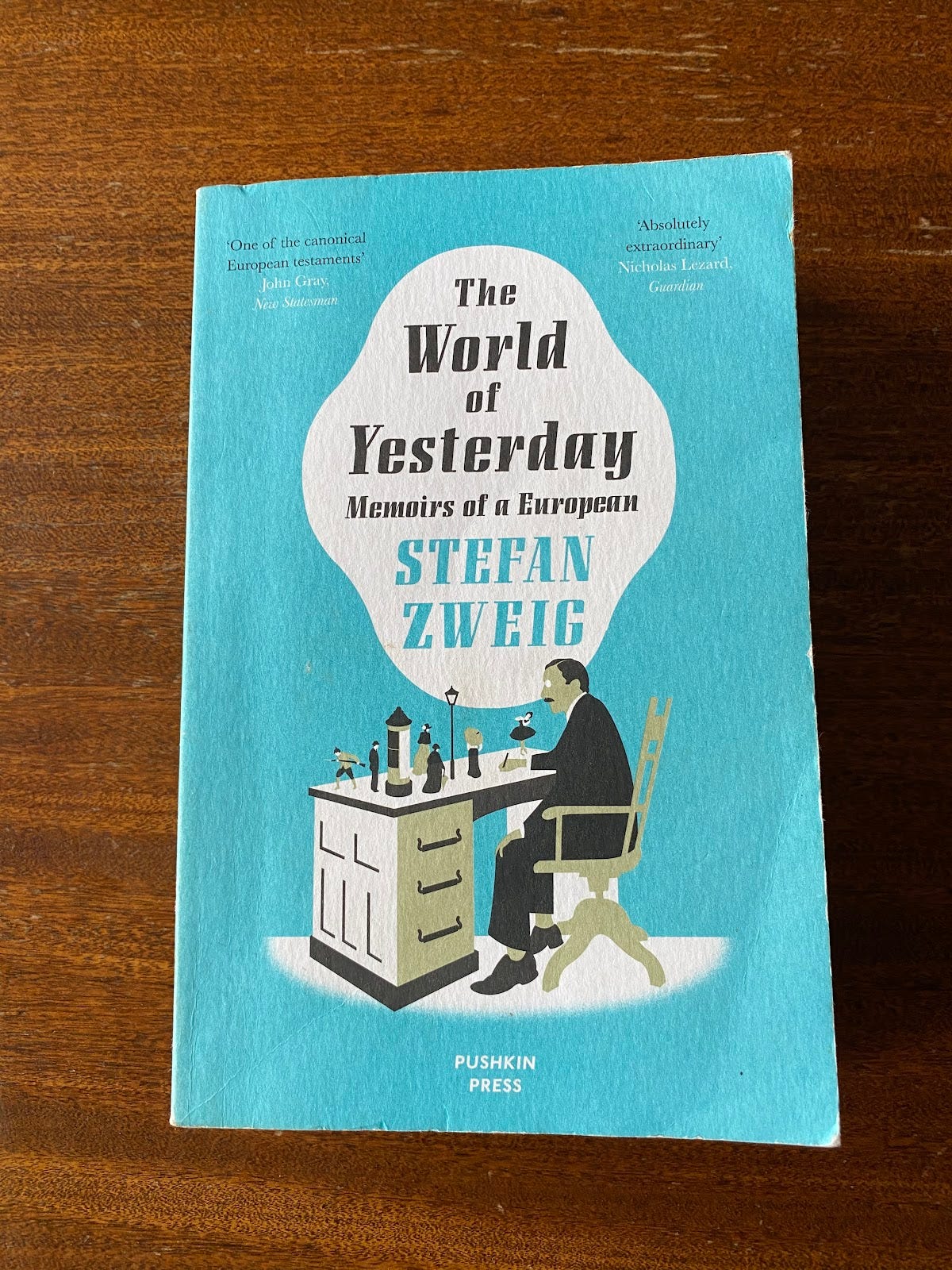

This house belonged to Stefan Zweig. Or perhaps I should say he belonged to the house. Either way, it was a brief relationship. He lived there only a few months, in the first year of WW2. I’ve come here because last year I read his book, The World Of Yesterday. This meant a lot to me. I normally read around 25-30 books a year, but between April and December 2020 I only finished two. As I failed to come back to one novel and one non-fiction book after another, I realised my attention was shot. As lockdown lifts, supposedly with so much time on my hands, I have very little to show for it. For two months, I wasn’t even working, but I had no capacity to concentrate. Amid all this, Zweig stuck.

It was no accident, I think. First, The World Of Yesterday is a memoir. When the present feels inescapable and the future unthinkable, it’s unsurprising if we’re drawn to look back. Perhaps it’s all we can do.

But The World Of Yesterday is more than that. It documents a lost world, a lost time, loss. Zweig came of age in Vienna around 1900. He drank in the same cafes and went to the same concerts and read the same newspapers as Mahler, Freud, Klimt, Schoenberg, Schnitzler. Vienna was a scene, dynamic and exciting. He saw himself as a “citizen of the world” and became one of the most famous and most widely translated writers of his day, a critical node in Europe’s literary and artistic network. He wrote biographies, plays, novels and memoirs. His writing is full-bodied and flowing like Rhine wine and marvels at what a civilised, curious, artistically fulfilled Europe had produced, could produce. And yet, during his lifetime, Europe fell apart. It destroyed itself and buried Zweig’s world, not once but twice. The first time almost by accident, the second with deliberate and murderous intent.

A book isn’t only about its own time. It meets us where and when we are. I’d found my copy in a charity shop before the pandemic, when we already understood a future outside Europe awaited us, whether we wanted it or not. The idea of a tolerant, open, poetic hymn to internationalism - and an eloquent denunciation of nationalism - was very appealing. That’s exactly what those early passages provided: beautiful stories of a peaceful continent and its culture, one foreshadowed by darkness.

But soon after buying it, all the certainties of our own time fell away too. Suddenly, The World Of Yesterday was a way to think constructively about what we were losing and consider what might come to replace it. Zweig’s book resonated because it was both an escape from and an echo of what was happening. With other books, the real world was so full and big and scary it could crowd out whatever I tried to distract myself with. Or maybe it was that events were simply so big that I owed some unspoken loyalty to the enormity of what was happening.

Either way, it was somehow reassuring to read something that spoke to the convulsive context without actually being about it. I could process what was happening without having to think about it. The book was a haven, a mood, a safe space.

Then I discovered Zweig had lived in Bath. The house is not only less than an hour from where I live, it was moments from where I’d been working as the pandemic struck. I had looked at the hills that hid this house as I arrived on the train every morning. I saw them every day from an office nestled in that south east corner of the city near the station. With lockdown, the commute stopped. Then, as I was made redundant, so did the job. I had time on my hands and a lot of worry and a difficulty concentrating. That the World Of Yesterday - a memoir of a disappeared world, a story of upheaval and a book that I’d loved and actually managed to read during lockdown - was written by a man living a stone’s throw from the business that had afforded me the time to read it, seemed too serendipitous not to act on.

I had to see the house.

I’m wary of overstating the parallels between 2020 and Zweig’s post-war years, though they were there. History doesn’t always feel historic as you live through it, but 2020 did. Covid commingled with the previous' years’ seismic political change and a rising nationalism of a kind that Zweig would have opposed passionately. Of course, Covid is not war, and few wars are like the European conflicts of the early 20th century. But the UK felt in the grip of jingoism. A proto-fascist administration controlled the US. All nations were locked into a crippling isolationism triggered by a global public health crisis.

But what resonated most for me was the dialogue Zweig creates between the innocence with which people had once lived, the upheaval that trampled it, and the prospect of the fall-out that might follow. Zweig vividly describes the good times and the bad, and perhaps in the end The World Of Yesterday is a weighing of the two, a reflection on how time allows you to see each differently, more wisely perhaps, or just with greater clarity. As with our own moment, good times became simply ‘before times’. Bad times start to resemble the consequences of complacency.

But amid all this, the hope. The excitement, too - beauty, even. At the lowest point, for Zweig, art endures. There is invention. New ideas flourish. I needed to hear that this was possible in 2020, and acknowledge it more so now. There’s a run of pages where Zweig describes what it was like to return to Austria once the Great War had ended. He finds a country ravaged by poverty and economic chaos, hyperinflation rendering money meaningless. Yet somehow the human instinct to make life meaningful remained. This is the section of the book I go back to the most, the one with most corners turned. He writes:

“We got used to the chaos and adapted to it. The will for life to go on proved stronger than the instability of the currency. Regardless of individual fates, the flywheel of the mechanism kept on turning the same old rhythm. Nothing stood still. The baker baked bread, the cobbler made boots, the writer wrote books, the farmer cultivated the land, trains ran regularly, the newspaper lay outside your door at the usual time every morning, and the places of entertainment, in particular, the bars and the theatres, were full to overflowing. For with the daily loss in value of money, once the most stable aspect of life, people came to appreciate true values such as work, love, friendship, art and nature all the more, and in the midst of disaster the nation as a whole lived more intensely than ever before, strung to a higher pitch. Young men and girls went walking in the mountains and came home tanned brown by the sun, music played in the dance halls until late at night, new factories and businesses were founded everywhere. I myself do not think I ever lived and worked with more intensity and concentration than I did in those years. What had been important to us before mattered even more now. Art was never more popular in Austria than at that time of chaos. Money had let us down; we sensed that what was eternal in us was all that would last.”

“What was eternal in us was all that would last.” Somehow, when what supposedly held everything together fell apart, what really held everything together came into its own. It’s beautiful.

But conviction like that among a people is hard-earned. You have to come out the other side of something hard. It breeds resentment. It divides. Looking back, Zweig sees how much Europe looked to its youth:

“In so far as the eyes of the world were open, it saw that it had been betrayed. All of us who had dreamt of a new and better world, and now saw the old game, on which our lives, our happiness, our time and our possessions were staked, about to begin again, played by the same gamblers or new ones - we had all been betrayed. Was it not understandable for the new generation to feel no respect for their elders? None of these young people believed their parents, the politicians or their teachers. Every state decree or proclamation was read with distrust. The post-war generation emancipated itself, with a sudden, violent reaction, from all that had been accepted. It turned its back on all tradition, determined to take its fate into its own hands, moving forcefully away from the old past and on into the future. An entirely new world, a different order, was to begin with all these young people in every area of life, and of course it all started with wild exaggeration. Anyone or anything not their own age was finished, out-of-date, done for. Every form of expression, including art, tried to be as radical and revolutionary as possible. The new painters declared everything done by Rembrandt, Holbein and Valazquez out of date, and embarked on the wildest of Cubist and Surrealist experiments. In every field, what could be understood was poorly esteemed - melody in music, a good likeness in portraiture, clarity in language. The definite article was omitted, sentence structure reversed, everything was written in abbreviated, telegraphese style, with excitable exclamations. Music persistently strove for a new tonality, splitting up the notes; architecture turned buildings inside out; in dance, Cuban and black American rhythms replaced the waltz; fashion, emphasising nudity, came up with more and more absurdities; Hamlet was acted in modern dress and tried to express explosive drama. A period of wild experimentation began in all fields of art, in an attempt to overtake all that had ever been done in the past in a single mighty bound. The younger you were and the less you had learnt, the more your freedom from tradition was welcomed - ultimately, this was youth triumphantly working off its grudge against the parental generation.”

A story of before and after has to break, and sides must gather along that divide. Zweig describes young vs old, the villains vs betrayed. Before and after becomes a story of inheritance and resistance. How powerful this is, to read of his enthusiasm for that next generation’s resistance, to imagine today what we might make of what remains. Today, talk of a return to normal seems inadequate, complacent - normal was nowhere near good enough. We need imagination, not a faithless reanimation of the old. Zweig warns us to be watchful. Keep an eye on those with influence over what our recovery looks like. Normal should give way to something less predictable.

Maybe it will feel like this:

“What a wild, anarchic, improbable time were those years… an era of frenzied ecstasy and chaotic deception, a unique mixture of impatience and fanaticism. This was the golden age of all that was extravagant and uncontrolled. Any kind of normality and moderation was rejected. But I would not like to have missed experiencing that chaotic time, for the sake of either my own experience or the development of art. Advancing, like all intellectual revolutions, with orgiastic energy in its first fine frenzy, it cleared the air of musty traditions, discharging the tensions of many years, and in spite of everything its audacious experiments produced some valuable ideas that would last. Uneasy as we felt with its exaggerations, we sensed we had no right to condemn and reject them arrogantly, for at heart this new generation was trying - if too heatedly and too impatiently - to make good our own generation’s sins of omission when we cautiously stood aloof.”

I don’t know about you, but in 2021 I feel ready for an intellectual revolution. I want the air cleared, tensions discharged, audacious experiments and, yes, the “first fine frenzy of orgiastic energy”. I want the world fired by Zweig’s vision of art, culture and politics, his humanism, his tolerance, his curiosity for the new. I want our musty traditions cleansed and a greater sense of wonder. But I worry, deep down, that it’s too easy to want this. For most of my life, I have experienced history at one remove. I have “cautiously stood aloof”. Zoom out from history and it’s easy to see the value of upheaval. You only see its destructive power if you get up close. What would it mean to have a ringside seat? What would be at stake? How sure can anyone be they’re doing the right thing?

In the end, Zweig’s vision couldn’t last. Europe turned on itself again. History repeated, stupidity reincarnated as evil. Zweig made his escape again. First to England, to this house. Then to Brazil and a house called Petropolis, high in the mountains outside Rio. It’s a museum now. Zweig’s legacy is listed on Trip Advisor. Apparently the staff are pleasant and there’s a cafeteria at the back. It seems a very long way from this sand-coloured family home, standing quietly in the English fog and a mystery of my own making.

The final escape was also self-induced. Zweig died by suicide, in a pact with his second wife, Lotte. It was 1942, the same year The World Of Yesterday was published. It being a memoir, this tragedy doesn’t appear in the book, so the full horror lives elsewhere, in the mind of the reader, who knows more than Zweig about how his story ends. There’s a picture somewhere, grainy and intrusive, the two of them lying side-by-side, spooning almost. My urge not to look at this photo is as strong as the urge I felt to come to Rosemount. But maybe I should look. Maybe not to look is to cautiously stand aloof. Zweig was Jewish. All Jews had a reason to escape Europe then, but he had the means. Millions didn’t. Was it guilt, what he did? Or was it that the world he loved was lost forever? How moral do we want our artists to be? There were those who suggested he didn’t do enough to fight the Nazis. That he fretted about the loss of his fame when he should have used it, was more concerned with that than the massive loss of life. After he died, his reputation suffered. Few read him after the war. He was, in today’s parlance I suppose, cancelled.

These fluctuations in fame and legacy are apt, I think. At what point should you judge a person, their actions, their time? Zweig’s ideal Europe was a time before the fall, a time of innocence and of a free exchange of ideas. But that moment also held a threat - that people would take it for granted. The convulsions of war were, of course, terrible, yet they unleashed a wild, revitalising energy that fuelled a new kind of recovery. A story’s lesson depends so very much of where you draw its end.

So what should we make of Zweig? A man able to look back but not, in the end, forward. A writer who was able to explain the world that had shaped him just as he chose to leave it. Perhaps the better question is what can he teach us? At the break of our own before and after, what should we inherit, and what should we resist? There are some lessons only history can teach us, which seems unfair, until you remember it can go on teaching us long after it’s gone. Maybe history never leaves us. It’s always there, and it will continue to be made.

Yesterdays are yesterdays because tomorrow came. And tomorrow will come again. What we make of it is up to us.

So sorry to hear about the loss of Brian. David Keenan's eulogy is lovely, as is this essay that I enjoyed just as much this time around. A fitting tribute.