The trouble in the end, it makes you anxious

Massive Attack recently played Bristol again, with a very clear message to the world. But being a hometown fan is complicated.

There is a moment. History seems about to repeat.

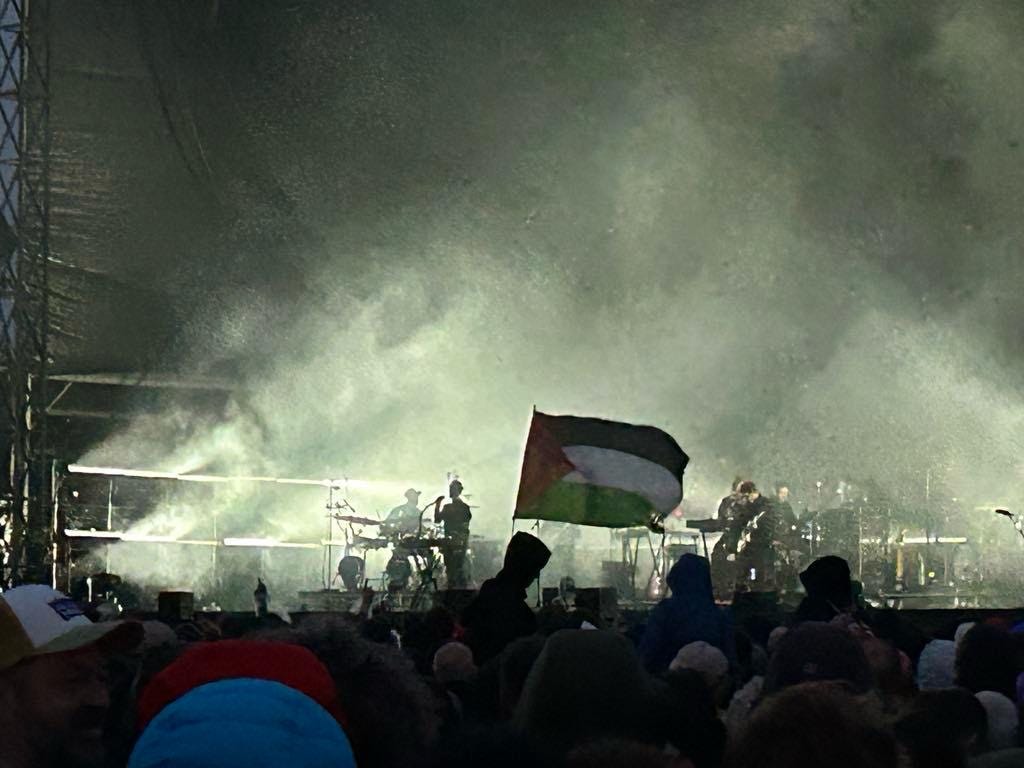

We’d known it was coming. The sun hadn’t shown up for its shift and spent the afternoon loitering behind an overcast sky. Now night-time beckons. Now an ominously dark cloud hangs above us. On stage is Motaz Azaiza, a Palestinian photojournalist. On the screen behind him are his images: devastation and horror and every part of me wants to turn away but I can’t. Gaza. The photos are enormous. Unignorable, as they should be. Azaiza thanks Massive Attack for letting him speak. He shares what it means to be here, to have been there, to have to look on as the world looks away. As he introduces the band, a breeze picks up. The dark cloud cracks. A cool rain hits our faces.

We look at each other: again?

The last time Massive Attack played here, in 2017, we’d been so smug. Then karma struck. Having imagined a relaxed day out, we got The Rain. Some of us are still damp from the rain upon rain upon rain we had that night. All throughout the set it fell. Mention it locally, you’d assume we’re all contractually obliged to call it ‘biblical’. It’s not law, but it is lore, how The Rain’s intensity increased afterwards. How it lashed us the whole walk home.

You should know that when I say ‘here’, I don’t mean Bristol. I mean ‘the Downs’. Durdham Down is a flat expanse of green at the top of the city, dotted with clumps of trees and perched high above the bank of the Avon. Imagine Hampstead Heath on a smaller scale, though large enough to let your dog run loose, or set up camp for a sunny day, or host football training on a Saturday or run. Large enough to fool you into forgetting that wherever you came from to get here, you got here uphill. Large enough to surprise you with the view at its far end of the Avon Gorge, rugged, non-urban. You may sense how exposed it is here then, how the wind whips down the gorge so the rain shoots sideways. Sometimes, if I’m feeling fanciful, and I imagine Bristol is our San Francisco, with its lolloping hills and green spaces, its wannabe tech businesses and fetish for artisan coffee and beer, the soggy microclimate tempering its otherwise sharp progressive radicalism, I see this exposed spot as our windswept toy-town Presidio. You can even see the bridge. You can really feel the rain.

For the avoidance of doubt: a bit of rain, with those images on screen, is the dictionary definition of a first-world fucking problem. It’s just that, well, we wanted some nice weather. A summertime sound-system. A Massive Attack vibe. It is, after all, August Bank Holiday Sunday. But no. It is August Bank Holiday and the rain is building and there is a genocide to confront and Massive Attack open with Risingson, Girl I Love You and Black Milk. It is late August and as we listen I realise Massive Attack have always sounded like September: liminal, a mood between realms. Music that faces both ways at once. All those half-floors.

Have you noticed their music depends on how you encounter it? That your mood makes them paranoid or chilled, soulful or dissociative? Tonight Massive Attack are all this at once. A gloomy August. Oppressive, but delicate like autumn air after rain. All rumble and menace, floating in an ethereal dream. It’s the best I’ve heard them sound in years. Huge aural planes reverberate as night darkens and rain and smoke swirl in the bright lights. That opening salvo is deep and wide, punishing and groovy. Pragmatic, too - a way to greet the returning characters one at a time, like scenes in a film sequel: 3D and Grant, then Horace Andy, then Elizabeth Fraser. Hello, darkness, my old friends. They do Take It There, Grant taking Tricky’s lines, then follow it with three songs performed with Young Fathers, who add yet more intensity. 3D introduces them as “our brothers-in-arms”. It’s thrilling. All drama. For the first time in forever I am watching Massive Attack in Bristol and caught up in doing so.

The rain stops. End of Act 1, is how it feels.

There is always drama when Massive Attack play Bristol. Their music is tense and conflicted anyway, but when their edgy claustrophobia is rendered among people, outside, out-sized, the tension gets bigger too. The atmosphere of intimate, smoky rooms scaled up to something monumental and very, very public. This tension is even more pronounced in Bristol, because a lot more is going on, much of it left unsaid. Each show stands for something. Every homecoming is a fight to change the city. Massive Attack push us a little further each time.

This year’s Downs gig was to push us and the music industry on climate change, and prove the viability of a carbon-neutral festival. An experiment like this was only possible because of that night of The Rain in 2017, which was the first time anyone had ever played on the Downs. Before that, nimbyism ruled. Massive Attack pushed, and it happened; we’ve had a festival there (almost) every year since. Prior to that, Massive Attack hadn’t played Bristol in twenty years. This wasn’t a scale thing - a chance to sell thirty thousand tickets on the Downs rather than the three they’d get at the city’s biggest venue, the Beacon - because Massive Attack have never played the Beacon. When I first saw them in Bristol, in 1998, as Mezzanine came out, they did a four-night residency at Bristol University’s Student Union rather than play there. This is because back then and until very recently the Beacon was the Colston Hall - named for the man whose city-centre statue was toppled by protestors back in 2020. The good people of this city rolled his hollow likeness to the spot on the waterfront where not-very-long-ago-actually slaves would have disembarked, and then they rolled his likeness over the side, plunging it into the harbour water. Largely thanks to that event, but also to the swelling, years-long momentum that exploded in that moment, Colston’s name has, finally, been largely expunged from the city’s buildings and its institutions and streets. Massive Attack pushed that too. They called out the incontestable history of that name and boycotted the venue for years because of it. Rumours of this stance was how I learned who Colston was. This stance was how I learned who Massive Attack are.

Massive Attack don’t let people off the hook, not even - or especially - if you live in their city. Descendants of immigrants, they are militant and definitive and unapologetic. Massive Attack are not at all the back-to-mine reality-escapists they’re assumed to be by people who are and who put Blue Lines on for a comedown once in 1992. They are not cosy or chilled or laid back. They are not t**p-h*p. They’ve shown us this over and over. Yet whenever they announce a gig here, people revert to a less complicated idea of who they are. Massive Attack, innit. Yeah man, Bristol. Here is real tension. Because despite having only two members left and no new album in 15 years, Massive Attack are not Oasis. (Their last album, Heligoland, was released in February 2010. Yes, under the previous Labour government. I like to think of this as a refusal to release albums under Tory rule. Another delicious, if unwitting, boycott.) They are a going concern, a globally successful live act, but really these days they are activists. You won’t relive your or anyone else’s youth at a concert of theirs. If you’re turning up for a hit of nostalgia, you’ve not been paying attention.

That much was clear the last time they played here, in 2019. Two years after The Rain, two nights at a temporary hangar at a disused airfield in Filton. Special buses, with MASSIVE ATTACK emblazoned in orange on the destination display, brought people from the city centre. It was like Jamie Reid’s Pretty Vacant artwork had come to life, or a fake terrorist incident staged by Jeremy Deller. A city-wide spectacle.

The gig commemorated one of Massive Attack’s albums by playing it in full. Lots of bands do this. It’s a way to meet fans where they are and pre-engineer the ritualised hedonism so many seem to want from gigs these days. This isn’t all bad. Nostalgia weighs us down as we get older, and gigs like that offer an outlet for it. They turn the object of nostalgia into something real, something present, something beautiful.

Obviously, that’s not what Massive Attack did.

First, they chose Mezzanine. Their third record, the one that caused Mushroom to leave - the escape from t**p-h*p that deliberately lost them the casual coffee-table listeners brought in by sounding mellow on This Life or whatever. Mezzanine is - because they are, and because how else do you escape the labels people want to put on you - spiky, morose, awkward, and it felt like that in the hangar too. Something was off. At first I thought it was that the warm-up music was awfully quiet. Then I realised the warm-up music was awful. S Club 7’s Reach For The Stars, followed by Never Ever by All Saints, then the Spice Girls. The DJ for Massive Attack, a group with its roots in sound-system culture, was filling the temporary venue not with hip-hop or dub or even the post-punk sounds that so shaped the album we were there to celebrate, but with late-90s pop music. This was deliberate. This is what you were really listening to in 98, it said. Back in your youth, this is what you guzzled wine and danced and snogged and pulled to. This was Bristol life, really. All those post-pub clubs on the Triangle, undernourished egos, four rotating hips, this is what they sounded like. This was nostalgia dampened with an unwelcome dose of reality.

It felt confrontational and petty, but funny. When accompanied by the visuals, it felt like an accusation. The gig was a collaboration with Adam Curtis, who was in full “...but that was just a fantasy” mode. You left feeling told off, if not for siding with oppressors, then for being stupid enough to be taken in by them. As for the music, I longed for such haranguing, but it was too quiet. Another exquisite torture, to fail to be overwhelmed like that, and to be subjected to the mounting background chat of an unsettled crowd as Massive Attack played the album in the wrong order and played unannounced covers of the songs sampled by each track. For Risingson, the Velvet Underground’s I Found A Reason. For Inertia Creeps, Rockwrok by Ultravox. Massive Attack do sampling more subtly than many, wrenching small sounds from their original and obscure context. Playing the originals live reversed this process. By not telling anyone, they presented an audience with tracks they didn’t know and which bore limited resemblance to songs they did.

It all added up to a strange, alienating experience. You didn't quite know where you were. Up or down. All these half floors.

At least the hangar was dry.

Maybe Massive Attack trusted their audience to know what was happening. I’m not sure many clocked it, or even realised it was a Mezzanine-only show. A ticket was just a chance to be part of the spectacle. Massive Attack, innit. Yeah man, Bristol. It had worked at Banksy’s Dismaland, a few years earlier in nearby Weston-super-Mare. But this time the crowd weren’t in on the joke. Maybe we were the butt of it.

And, I get it. I didn’t wholly enjoy the choices, but I admired them. It appealed to my misanthropy, and to my gatekeeping tendencies: a group trolling their own audience in a way that cost them something - namely, the vibe of their own show. Massive Attack leaned into the tension that exists when they play. It was an exposition of the disconnect I’ve seen up close: the misaligned expectations, the hometown refusal to accept who they really are. I remember one guy back in 2017, a proper festival bro. You know him. He spreads his arms and points finger-guns at the sky to a song he recognises. He shouts “oi-oi” to celebrate a mate’s successful return from the bar. He wears shades at night. Gets bored easily, especially if he’s not hearing what he thought he was going to, or if the party vibes he was expecting don’t transpire. He might dip his shoulders and wheel around in frustration, shout ‘for fuck’s sake’ at people near him. Might shout ‘play the hits’ - at Massive Attack, whose ‘hits’ that are downbeat and sad and tense. This was what stood in front of me for the final third of the 2017 Downs gig. The Rain and that guy. Massive Attack can troll him all they want.

There are others. The guy not so out-of-it as festival bro, but more vocal about not wanting “politics shoved down my throat”. The muso who didn’t get 100th Window and reckons they’ve “disappeared up their own arse”. The middle-class, middle-aged types grumbling that the sustainability message “got drowned out” by Gaza. I wonder if this swirl of expectations is present at other gigs on their global tour. I wonder if someone in Dusseldorf or Tblisi or Buenos Aires wants them to play the hits and cut the politics, or prefers their own idea of Massive Attack to the reality. I suspect people in those cities feel compelled to attend Massive Attack gigs precisely because of the solidarity they feel with the band’s politics, and with their musical evolution. The way you do when you love a band for who they are, not where they’re from.

As far as I know, Massive Attack still live here (I’ve seen Grant out with his kids and at gigs; they got vocally and visibly and righteously behind the local Green Party candidates in this year’s General Election), but I wonder whether they really belong to Bristol anymore. Their real constituency today is that global audience - the ‘citizens of everywhere’ united by worries of war and power, marginalisation and surveillance. These Bristol shows are part of a tour that now and again land in a place that happens to be their hometown. They platform and play for people for whom Safe From Harm was always literal - for whom lines like “if you hurt what’s mine, I’ll sure as hell retaliate” are more than just a hook. As they dedicate this song on the Downs to Palestine, it’s very clear whose side they’re on. They’ve always looked out for people with no voice. Have always, like all good activists, applied their leverage where it works.

Which in their case, is here. On us.

That’s why Massive Attack confront us the way they do. They confront us with the reality of what it might mean to live elsewhere, and with the extraordinary privilege and painful responsibility of our freedom. Confront us with the dehumanising, deleterious effect of the technology we have allowed into our lives, and which oppressors use to keep their populations under control. During Black Milk, cameras pick out individual faces from the crowd and show them as live images edited into polaroid squares that shoot around the backdrop. You see people react to themselves on screen, the way people do at sports stadiums. It’s uncanny. It is surveillance dressed up as entertainment. Or the other way around. Maybe all this is 3D’s grafitti artist instinct: provocations painted in augemented reality, not spray paint. Whatever it is, a handful of phones appear in shot, because the Pavlovian response these days to want to capture the moment. No doubt some of the pictures they take will be shared on social media - that way people who weren’t there will know the taker and subject of the photo was. Such is life now. We affirm ourselves in a two-way digital black mirror. So full of uncertainty and fear and anxiety are we about our place in the world, there is safety in being seen, no matter what it costs us. “I was looking back to see if you were looking back at me, to see me looking back at you,” as someone once sang.

Massive Attack model how to look both ways constructively. They prove it is possible, imperative even, to look out into the world and then back to where you came from and find your hometown wanting. They suggest that unless you see the oppressive systems of the world for what they are, you’ll struggle to look the oppressed in the eye. They are militant activists making ambiguous, beautiful music. Humanists who struggle with people. They make a safe space of dislocation. They make anxiety make sense. They are oblique and strange and ambiguous and in these damaged and precipitous times that somehow makes them universal. They are what the world sounds like now.

When they play Risingson as the opening song on the Downs, the darkness closes in like a cloak, the song seems to billow and breathe like the cloud hanging over us. It is alive but ominous, familiar and uncomfortable. It pulses with dissociative anxiety. Dark energy everywhere. When 3D sings about feeling “lost and lethal”, you kind of know what he means, even though he will never explain it. You kind of imagine lots of other people know what he means too, even if they did dance to S Club back in 1998. Everyone feels separate sometimes. That’s why there is Massive Attack. They are for when the world doesn’t fit. For the struggle through the dub daze. For the glitches, the moments of doubt. For thinking you’re the only one awake as the rest of the world dreams on.