Terrains piled up like collage

A freewheeling trip around California leaves your head spinning. Here's what it's like to scratch at the surface of America.

I want to write about America because I went. I want to write about America but how.

Write about what you know, they say, but how can you know America? How can anyone? Three weeks was all it was. Hard to feel I have the right. A California road trip. Flying visits and freeways - barely time to scratch the surface. Actually the surfaces. The contours of California’s vastness, terrains piled up like collage. Forest and mountain and beach and cliff and desert. Cities any kind you want. Heads spinning, wheels rolling but how to compute any of it. How to not crash but still look and take in what you can. How to make the intersection in time. How to remember.

Wide-eyed we looked. America stared back on high alert. This was days after Biden pulled out. We landed in San Francisco and the middle of a whodunnit, months from discovering the body or knowing which one it was going to be. Inflation wasn’t yet a suspect. Do they say ‘it’s the economy stupid’ every time? Is it always a surprise reveal? I guess it depends what you mean by the economy. I’ve seen headlines claim ‘US economy is set to grow but jobs and wages remain stagnant’. Which begs the question, what is the economy for people who write about it if it isn’t jobs and wages. A category error. Hiding a wallet-full of others, no doubt. But sure, continue to ask ‘are you better off than four years ago’ as you step over the comatose on Market.

San Francisco is a city of millionaire liberals and desperate people and is Kamala’s home town. I’m not sure how you are supposed to reconcile this. I’m not sure, if you run for President, how you establish any degree of control or consensus, let alone mastery or power. Lies? Stories. There are people lying on the ground yet no one sees them. Driverless taxis yet people get in them. How to explain this to your kids. How to explain to your teenagers the thrift stores with nothing they can afford. Is it inflation, or the tourism effect we’re pretending not to contribute to, or an economic micro-climate made by the internet that puts second-hand Levis at $100? Is it the cost of housing, or a Fentanyl epidemic, or a self-defeating myth of self-reliance that took away the safety net? How do you blame immigrants in the face of everything, in the face of what America was, is, has always been. Later we visit The Broad in LA. Enduring American art: Warhol, Basquiat, Koons. Enduring American artforms we see everywhere: cognitive dissonance, selective sight.

Also benefaction. America has made charity a pageant just like everything else. The Broad bears the name of Eli and Edythe Broad - entrepreneurs and art collectors and, now, according to the building at 221 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles and the scores of million-dollar artworks within, philanthropists. In California, everywhere is named for someone. A landscape of honorifics, legacies and claims. Signs in the key of history. Mulholland Drive. Huntington Beach. Mission District. The commemoration is everywhere. America is an open-air exhibit of itself.

Pick any place. Say, an unscheduled stop near Mariposa. The drive from Lake Tahoe to Yosemite nearly done. Everyone hairpin queasy. Hot, dry air is all there is but we get out anyway. There on the ground - a stone. A monument to John Fremont and his “fight to defend this land”. Where do you even start? Do they fill in the gaps in school? Guy helps do over the Mexicans then gets rich from the gold then fails to become President and loses the fortune and sees out his days as Governor of Arizona. Gets a city in the Bay Area named after him. Fremont. You darn’ tootin’ people know his name. But his full story? You suspect by now selectiveness is the point. The selectiveness is what is everywhere. It’s on every surface.

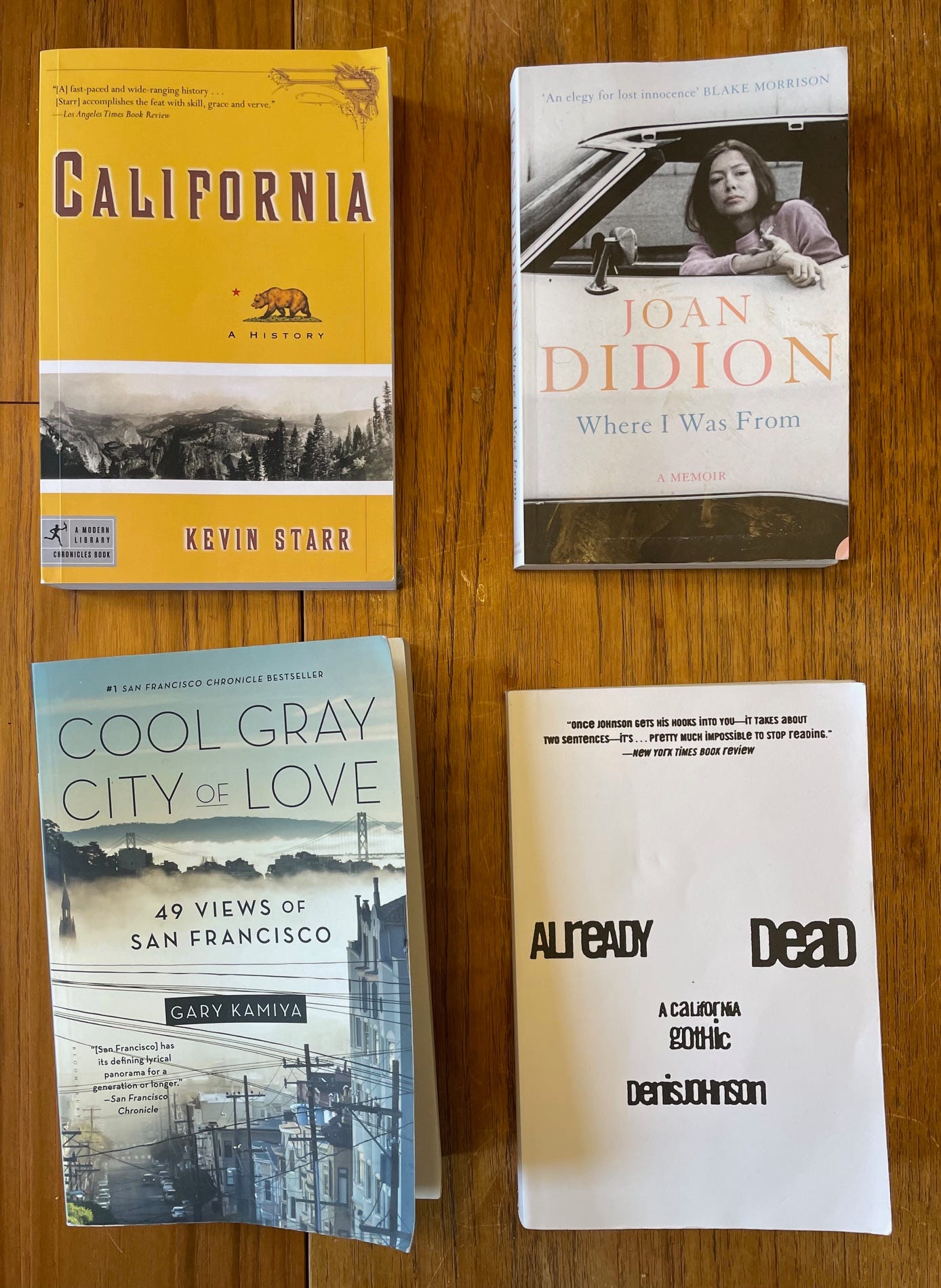

As we go I read Kevin Starr and Joan Didion, Gary Kamiya and Denis Johnson. History, journalism, fiction. Each a kind of truth. Each a way to scratch at the surface. I buy two of these books from City Lights and is that what the American Dream feels like? I read in three of them accounts of the tectonic shifts that made this landscape. Pre-history is a contemporary issue: life on the surface of California is still shaped by the ongoing rumble underneath. One plate still slowly shunts past another along the San Andreas Fault. In Joshua Tree they tell you the land moves at 50mm a year: the speed that fingernails grow. On the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway you’ll travel at 17 miles per hour to the cliffs of Chino Canyon. From there you can look back out over the grid of the city, see where the Fault scars the land beyond. It messes with your mind, such a scale. Widens the perspective. It can’t hurt that it stretches the timeline out to make a mere blip of the betrayal. Can’t hurt, can it?, to minimise America’s original sin, make it a molehill next to the real mountains. Except of course for the hurt that can’t be undone, is still yet to settle, is still resolving in fault lines below the surface.

Maybe California has selective sight because selective sight in a way made California. From the east, before gold, no one thought to look beyond the Sierra Nevada. The bay entrance, the gate of the west, fooled passing ships for centuries prior to that. Land here always was a trompe l’oeil. So, yes, earthquakes. But starting the story back then is just one more trick of the land. Another way to frame the view. To make the story geological not genocidal.

Didion worked out these tricks, the ones Californians play on themselves. She was from Sacramento. Her family were among the first settlers from the east. Gold prompted the journey, harshness defined it. Descendents of those first American Californians got their inheritance, which was the lesson that reward comes with resilience. That sacrifice is the key to success. But Didion saw the blind spot. In Where I Was From, she tells us:

The California settlement had tended to attract drifters of loosely entrepreneurial inclination, and to reward most fully those who perceived most quickly that the richest claim of all lay not in the minefields but in Washington. It was a quartet of Sacramento shopkeepers who built the railroad that linked California with the world markets and opened the state to extensive settlement, but it was the citizens of the rest of the country who paid for it. The citizens of the rest of the country would also, in time, make possible the irrigation of millions of acres of essentially arid land, underwrite the rhythms of planting and not planting, and create finally, a vast agricultural mechanism in a kind of market vacuum, quite remote from the normal necessity for measuring supply against demand and cost against return. These are the kinds of contradictions on which Californians tend to founder when they try to think about the place they come from.

Didion knows Californian inheritance is a kind of generational brutality. It is born of selective sight, a story passed on as a damaging myth. If persistence and imagination were enough to make the desert bloom, what would it mean, then, to need help? What would it mean to provide it? Both stand for weakness. Americanism is, in the end, about strength. Preserving the myth means making an enemy of weakness. It means being fearful of the weak.

One day, like America did once, like America does now, we go in two different directions. We leave Huntington Beach in stages. Two for Anaheim by car, the rest not to Disneyland but to Oceanside. We go first by Uber to Santa Ana, then catch the train. The roads are jammed, the train is empty. Randy picks us up outside the hotel. We speak about politics. We trade lines on Trump and Harris. An education under John Oliver’s pedagogy pays dividends. Randy hates MAGA. My son and Randy are in violent agreement. Both are delighted. I sit back and cling like a limey as Randy rockets down the freeway. It’s faster with Randy driving. Every Brit who comes here talks about food portions - it’s a kind of scale for the scale. For me it was the speed limit, which was interpreted less as a limit and more, like the food, as a serving suggestion. Drivers supersize as soon as breathe. Randy hates MAGA. He is relieved about Harris. Very. He couldn’t and wouldn’t have voted for Biden. Randy swerves lanes, again, violently and without warning, barely thinking, it seems. I cling tighter still because I don’t get these rules.

Back in San Francisco, two views from the Bay. On the boat tour we get up close to Alacatraz, close enough to see the graffiti proclaiming it Native American land. Then someone points out Coit Tower, and we climb Telegraph Hill to see that up close too. The view from it is the best we get of the city, the views inside are even better. Lillie Hitchcock Coit loved San Francisco’s fire service and bequeathed a third of her money to the city. A tower was built in the shape of a fire house to honour her. New Deal cash decorated it. The art on the walls inside Coit Tower feels profoundly American but in a different way to Warhol and Koons. Farming and industry and city life and the nobility of work sing from the plaster. They are the most socialist murals you’ll see this side of the Zocalo. Pure Rivera, and with good reason: American painters were taught by him to paint those things, like that. So beautiful. So slender the boundary between socialist ideals and the rhythms of everyday America. How hard some work to keep them apart. Sometimes commemoration keeps an idea alive.

Sometimes opposites collide and the collision speaks. There’s a place on Route 1 called San Simeon. Look west and you’ll see the hippies: the commune at the edge of the world. Look east and a road winds up the hill towards Hearst Castle - the richest of all rich man’s playgrounds. A hiding place made of opulence and influence. Hubris and dreams. The basis for Kane’s Xanadu. He and the hippies are worlds apart but feel equally Californian. Their baseline belief is self-determination. The individual’s right to live by their own rules.

In hotel rooms and AirBNBs we tune to NBC. It’s the Olympics. U-S-A, U-S-A. Self-determination in excelsis. Boy does it get boring. We’re used to coverage full of sub-plots and drama and breakout moments. Go Team GB, but with jeopardy. NBC go deep on US athletes and insultingly cursory on everyone else. We’re shown the athlete’s family in the stands. We’re shown the backstory, the striving, the basking in success from last time, footage from training. We’re shown data on the Dad’s heart rate as he waits for the race and is monitored by the technology provided by the sponsor of this infotainment segment. Heart pumps to jerk heart strings. It’s like The X Factor only worse. No vulnerability. The only jeopardy: where will the American place. Eventually it dawns on you: America says it loves competition, but really it just wants to know it won.

Maybe that’s why someone always has to lose. In Los Angeles we drive to Griffith Park. The city looks best from up there. It sprawls out towards the coast and also inwards, ever inwards. Chaos, vastness. In the Observatory, they replicate Tesla’s electricity experiments, pioneer nostalgia sparked every 30 minutes. Outside the sun sets hazily over the Hollywood Hills, like a dream. Everyone here is a tourist. No one here is told that Griffith Park doubled as an internment zone for Japanese residents during WW2. How Pearl Harbour made them overnight enemies. How they were held without trial. Same thing on Angel Island in the Bay. Courtesy of Executive Order 9066, courtesy of FDR. The good one. America’s fear of the weak extends to failing to admit to the times it gives in to the fear. ‘This is not who we are.’ It very much is. The week we arrive, at the RNC in Milwaukee, Trump supporters hold signs demanding mass deportation. Belonging is contingent. Dispel weakness. There’s a reason there’s a cut. There’s a reason someone doesn’t make it. The threat of the drop must be real. How else will Americans know they’ve won.

Someone always loses, and in the end it was Harris. I guess the point of all this is I shouldn’t be surprised. The vastness is too vast, the perceptual skew too embedded. Selective sight won. As I stand next to the Observatory, I remember standing on another mountain, the one that looms over Palm Springs. I remember thinking about what it meant to see America from above. Is it the preserve of tourists, I wondered, to get one view from up here, one from down there, from within? What is it like to handle the scale of it all at the level of the teeming intersection? Can you screen it out, forget; or do you end up feeling forgotten? The distances are so big that from up there it felt like vertigo. But maybe what I was feeling up there was a vicarious kind of agorophobia. A fear of overwhelm. A worry where help will come from. Not for the first time I think that in a place as vast as America, all lives must feel small. How to not feel abandoned?