Returning to myself

It's been months since I've written here. But a performance of Joni Mitchell's music by Eska and the Nu Civilisation Orchestra was too good not to write about. Here's a review, of sorts.

The thought crossed my mind that, now we were here, the performance had proved too esoteric after all. Or that she was tired. I know I was.

We were in St George’s, all warm acoustics and stern pews, quiet taps, the odd polite cough, bows and music stands set in preparation. Deference in the air. Players ready to go again but waiting for cues from their conductor. The music had been glorious.

I could see her eyes were closed, though. Was she enjoying it?

Normally at a gig you aim for some quick affirmation, a sign you’re occupying the same emotional space. A little eye contact, a quick comment under the crowd’s noise. But we were sat upstairs, front row of the balcony, the corner of the stage disappearing beneath us, and I was in my friend’s blind spot. Me to her right, both of us looking diagonally left. A tap on the shoulder didn’t seem right. It was all so reverential.

Maybe this is how musicians listen, I wondered. I tried it myself, closing my eyes hesitantly, like a doubtful child. Wow. Instantly the sound came into focus. It was brighter, louder, all consuming.

She confirmed it at the interval: we were both bowled over. In the brief minutes we had to take stock, language inevitably fell short, but it was all we had and words tumbled out anyway. What a voice, we said. God, the music. My friend talked about how good it sounded, the depth of the music, the balance of the arrangement. The shape of it in the air. A good sound engineer does that, she said. We mentioned harmonics, too, neither of us quite sure what that meant. I stumbled through some hasty exposition in reply. Why we were here. What was happening. The players, the songs.

It was a joint attempt at a translation between our respective disciplines, between music and writing. The space where words fail.

It’s apt we were trying to bridge a space like that, as this was a concert defined by distance. The distance Joni travelled after Blue, those six restless, pioneering years that led her to Hejira and to the brink of Mingus - another land entirely. The distance too that Eska had negotiated between Joni’s performance of the music and her own, a distance that was all art, since it required a balance no sound engineer could provide, one that allowed Eska to plunge deep into the landscape of this music yet simultaneously rise above it, a “black crow flying in a blue sky”.

And another kind of distance, the one that separates then and now. The passing of time. The then of 1976 and the now of 2022. But also the momentary then of the concert, with our closed eyes and open mouths, and the slow now of re-living it through writing, thinking, hearing it properly. Somewhere between these points lies the meaning of this music. Or rather, the space within which its meaning can shift and evolve, as we allow ourselves to hear it, sing it, feel it all over again.

We drank more water, shared an orange. Neither of us wanted anything stronger, nor cared to ask the other why. It was enough to have stepped into St George’s, into Joni’s world, into Eska’s world too, and therefore through that portal, away for a brief while from whatever it was we each needed to be away from. Some small domestic chaos, no doubt. The usual responsibilities. And at least for me a certain stuckness. “It is necessary to write,” wrote Vita Sackville-West, “if the days are not to slip emptily by.” Oof. The sharp stab, the guilt, the sinking feeling of hearing that when you’re stuck – when you’re not writing. Although, that’s not quite what Vita meant, of course. “How else, indeed” she continues, “to clap the net over the butterfly of the moment? For the moment passes, it is forgotten; the mood is gone; life itself is gone.”

It's not only sound that brightens when we close our eyes. It’s not just the other person we connect to when share our thoughts. Something other than our word count grows when we write our way through it. The moment expands as we fix it. It is Vita’s moment. Life itself. Our enjoyment and appreciation of the fleeting, random, transient butterfly-ness of it all. We keep the mood from passing. Take it in. Connect to life as it happens to us. Bridge the distance between ourselves and the world.

OK. Some grid references. Eska is the British-Zimbabwean Mercury-nominated singer who defies categorisation and whose music encompasses jazz, folk, soul and electronica. The Nu Civilisation Orchestra is the project born of London’s Tomorrow’s Warriors jazz school, which tackles classical, jazz, soul, and anything else it can fuse and filter into new shapes. Together they took on the task of re-arranging and performing two of Joni Mitchell’s most strange and exploratory albums, Hejira and Mingus. And then playing it live.

Hejira is ten songs of stark, monochrome beauty, making up an album Joni herself described as about “the sweet loneliness of solitary travel.” It sounds at once flush with the sense of escape and engaged in the search for something. It’s renowned as the first Joni album to feature occasional daubs from Jaco Pastorius, the painterly bass player from Weather Report. But the dominant sound is Joni’s electric rhythm guitar, strident but isolated, like a hitchhiker. Unlike the full rich sound we heard in St George’s, there are rarely more than three people playing on a track. A first-time listener can be forgiven for feeling a little lost at first - we really are a long way from Blue. There are no choruses, or hooks, just stanzas of dense, elegant, whip-smart poetry that resolve in a refrain, frequently the song’s title. The songs descend there, unfurling in strange chord patterns, seeming to spin in slow circles, inching and spiralling around a spine like the centrally aligned lyrics on the sleeve.

Until you’re familiar with Hejira, its music can sound the way its sleeve looks: grey, endless, indistinct. (Is it dust bowl or frozen wasteland on the cover, or some imagined hybrid of the two?) Until then, you rely on the pencil-light, swooping repeating melodies that sketch the landscape, twist and turn along the way, Joni’s phrases guiding you like roadside landmarks. Hejira is not jazz. There’s no extemporisation, any interplay is in the background. Yet those feint traces of structure were hooks for the orchestra. They seemed to infer the jazz from within, drawing out what was otherwise only implied. Like it was encoded deep in the music. “Yes, that was the brief,” Eska confirmed. (Another unusual gig thing - when you go with a musician they don’t mind sparking a conversation.) “The thing with Joni Mitchell is,” she said, “there’s so much musicality wrapped into every aspect of what she does. We set ourselves the task of unlocking it.”

Was she daunted by the prospect? “I get it. I know what Joni Mitchell means to people. And it was a challenge. The first job was to learn it all. But at that point you realise she never sings the same thing twice.”

(Is that why, I wondered, those phrases-as-landmarks take a while to feel familiar.)

“But then you have a choice,” continues Eska. “Do you do it the same as she does, or something different?” For Eska, it was really no choice at all. “You have to bring something to it, otherwise it’s just karaoke.”

Maybe that’s why the gig felt so alive. It wasn’t a homage, or even a reinterpretation. The musicians gave the music space in which to become something new. Eska found new angles, new moods. The jazzification gave those spiralling Hejira circles the depth of grooves, patterns drawn in the desert dust (or gouged in the ice). What you hadn’t heard until now sounded like it had always been there.

The word hejira is itself a corruption of the Muslim word Hegira, and refers to Muhammed leaving Mecca for Medina. It translates as departure or exodus, or migration. A journey or flight. Joni chose the title, she says, because she wanted a word that meant “running away with honour.” For most of us, most of the time, travel is an escape. It was that for Joni too, you can hear it. Travel meant aloneness, a freedom - from relationships, from expectations - to which she felt and was entitled. But you can hear something else in Hejira too: an ambivalence, an unasked question. Is restless travel as healthy as it seems?

In Amelia she’s “driving across the burning desert,” reflecting on how subjective happiness is: “where some have found their paradise, others just come to harm.” In Coyote, the album’s best-known song, escape is also a constraint - each verse concludes with her “a prisoner of the white lines on the freeway.” Travel as an addiction. The idea is there in Strange Boy too, a very mid-70s kind of romantic road trip. “We got high on travel,” she sings, “drunk on alcohol.” The duality is clearest in the title of the final song: Refuge Of The Roads.

For Joni Mitchell at the time of Hejira, the best way to feel safe was to keep moving, but she also knew that what made her feel safe wasn’t necessarily the best thing to do.

At the time of the gig, the best way for me to feel safe was not to write this.

That stuck feeling was starting to take. Inertia creeps. Nothing bad, just not progressing the longer term project I’ve given myself. I’d lost the habit. I recognise my procrastination these days as a strategy to avoid disappointment; the view doesn’t seem worth the daily effort of the climb. To my brain, it feels like safety: protection against negative feelings. Words can’t fail if you don’t try to use them. As Joni sings on Hejira’s title song, a lyric Eska first read unaccompanied before singing it: “there’s comfort in melancholy, when there’s no need to explain.” She’s talking about the false security of a failing relationship, and how she’s “returning to myself, these things that you and I suppressed.” The feeling of not writing - no way to explain rather than no need - can be its own kind of melancholy comfort. It’s safe, until it isn’t. Something is suppressed. Time to return to myself, you think.

I figured the attraction of writing about Eska’s performance was the lure of the self-contained piece. Drafting something long, you have to resist the dopamine high (and impossible dream) of the perfect sentence. The temptation is always there to chisel and polish. But long writing needs a miner, not a sculptor. Your job is to hack at the walls, not refine stone in the studio. A quick essay, I thought, might give me the satisfaction of something complete. A hit. And besides, I have places to put something like this, places I’ve neglected. Here, obviously. But also here. So. A few notes, a first few paragraphs, let it percolate. Then tinker.

I got my dopamine hit, but not from where I thought. Yes, it’s nice to turn a pleasing sentence. But more thrilling was what else it gave me. The sense of the moment, diving deep into the performance and the new life it gave to Joni’s music, the magic of Eska’s performance, the feeling of everyone in that room. To briefly pause the world and concentrate on one small thing, and fix it, be properly in it. There. To write it over and over, to excavate on instinct, and have the instinct proved right. Like my friend closing her eyes to brighten the sound, or Eska herself, plunging into someone else’s work to see what it demanded of her own, it was a way to fully pay attention and take more away from the moment. It was the thrill of Vita’s butterfly net. Of catching the mood. Not letting life get away. It was the rush of the slow now, keeping the momentary then alive so that meaning could emerge in the space in between.

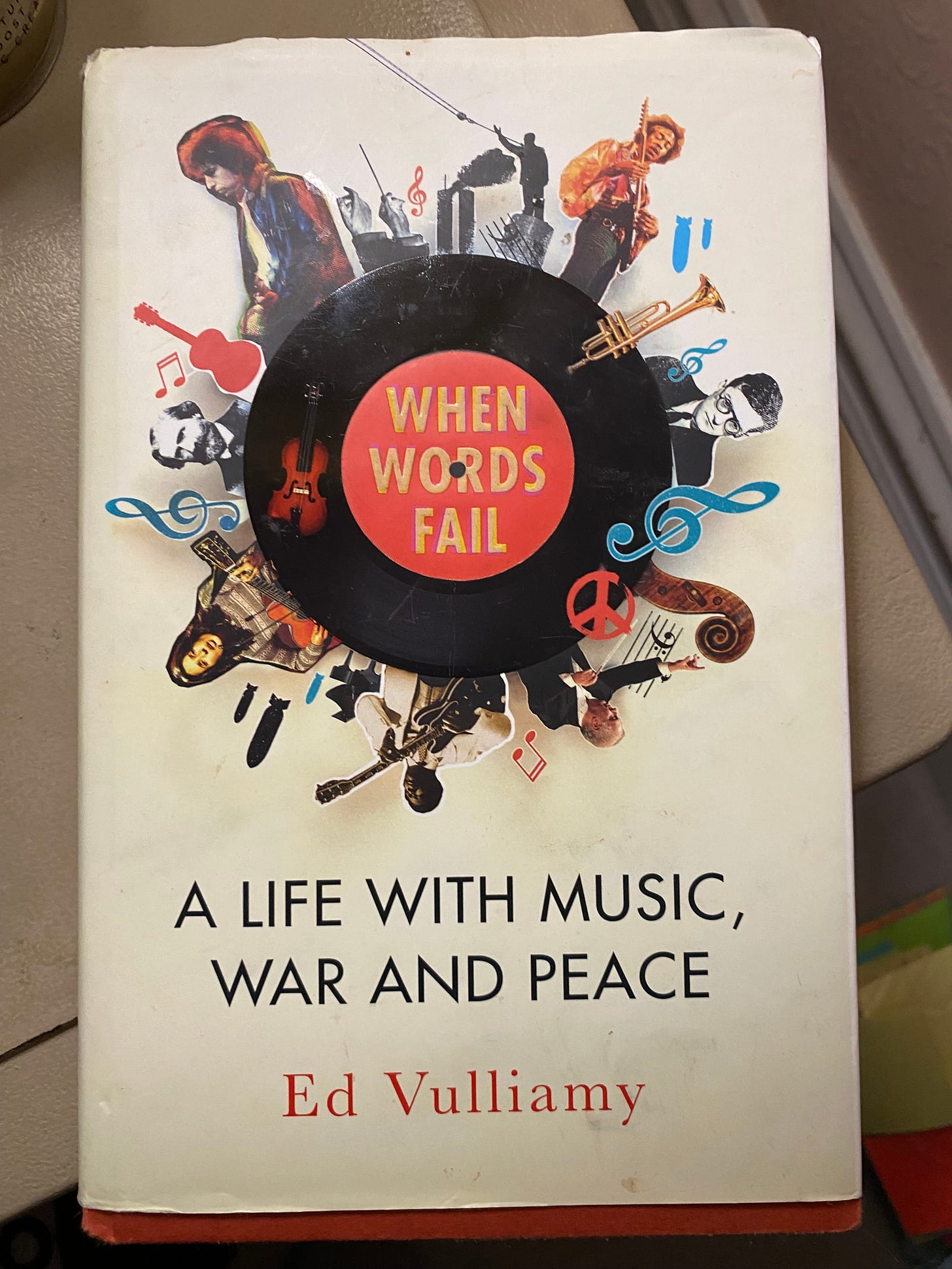

In a book I was reading while writing this piece, a book lent to me, as it happens, by the friend who accompanied to the gig, journalist Ed Vulliamy writes about his own experiences with music and connection. One chapter includes a mention of harmonics, the word neither of us had quite understood at the interval. Vulliamy explains harmonics are the ‘overtones’ in music that accompany a note. They sound at the same time, and we hear them as if they were real. But they’re not. Harmonics are notes that aren’t played. They are the elements of music that, in Blake’s beautiful phrase, are ‘unknown but not unperceived.’ Harmonics are not actually there in any intentional sense, but we feel them. They are the inner, deeper information encoded in the musician’s performance.

Does life have harmonics? I rather think it does. We begin to get at them when we really, really pay attention. Others may claim it’s projection, but really we’re drawing out the meaning that works for us.

Meaning like: Joni’s ambivalence about the world she inhabited then, the doubt that sounds like conviction. Life as a series of circular grooves traced in the landscape, that deepen every time we trace their shape. The idea that running away might bring you nearer to yourself. That the best way to get unstuck is to sit still for a while, and look. We see life better with our eyes shut.

The harmonics of life are always there. Just close your eyes and pay attention.