Lowering the threshold

Under the spell of Karl Ove Knausgård again, and an exhibition of painting inspired by his writing.

Eventually I accepted the inevitable and got out of bed for the second time.

It was already later than I’d intended, near enough 10.30, and there was something I wanted to do that morning, an event which the website said would run from 11am till 1pm. I wasn’t sure how the event was going to go, what it would require of me, how to correctly be for its duration and the occasion.

On top of this I felt queasy and groggy, hungover from having friends around the previous night.

We’d suggested a get-together during the week. Something about the speed and enthusiasm with which the Whatsapp acceptances came in said this was something everyone needed. We offered to make the food, asking only that the guests bring the drinks they’d like, or that they thought others would like.

Our friends placed the bottles on the kitchen island as they arrived, and come 9pm there was red wine everywhere, along with spirits and strong cider. My commitment to non-alcoholic lager crumbled the moment someone offered me a pre-meal espresso martini. Someone else brought Jack Daniels and Coke, the favourite late-night drink of another member of the group. We went with the flow. Everyone left around 1am.

By then I couldn’t face tackling the kitchen mess, but I knew at least two of the children would be up before us, our eldest son was working the next morning and would leave around 7, another is just an early riser, and I didn’t want them encountering this. I moved dishes and glasses and half-finished plates of food from the dining table and the kitchen island, making a mountain of dishes and glasses in one part of the kitchen. Then I went to bed, remembering to set my alarm so I could make sure our son got up and out OK.

Once he’d gone I drifted back to sleep.

I got up for the second time and went downstairs to make coffee. The debris of the night before was still there. I filled the dishwasher, prioritising the stuff that would stack without effort, plates, cutlery and glasses. I made toast for my wife, still in bed, and ate some of the courgette frittata I’d made last night. Coffee. It was now around 11.15. The nagging doubt about this morning’s event came to the forefront of my mind. Didn’t it start at 11? Was I going to walk into something already underway? The self-consciousness of the situation rose in me and I felt my casual resolve of the night before - just go, you want to go, who cares, it’s only people - begin to crumble, just as my commitment to not drinking had crumbled the night before.

My over-thinking threatened to swamp the moment, so instead I searched again for the book I knew I wanted to take with me. I am good at this kind of distraction, where two scenarios hold true simultaneously. I wanted to go, which is why I felt I should look for the book. I also wanted not to go, and so the search for the book was a kind of self-sabotage, a de facto delay that would make me late.

Some of our books are sorted by the colour of their spine, some by genre or subject. They’re split across five rooms. There’s no order to them, in other words, and the incredulity of a friend who recently visited (“how do you find anything, Jim, it must drive you mad”) pinged around my brain. The fruitless search for the book took me up and down stairs. I leaned down to read spines at speed. I happened across another book by the same author - one I hadn’t read yet, the second in his series of memoirs - and on instinct grabbed it off the shelf. I put it inside my shoulder bag along with my notebook. I brushed my teeth but didn’t shower, out of respect for the people I might meet, the bare minimum really, it was only local, after all.

I was getting dressed in the bedroom when our daughter came in. She wanted to know why the car wasn’t on the driveway and to share her disdain for the mess she’d encountered in the kitchen. We explained that her brother had taken the car and I apologised for the mess. “I hope last night didn’t keep you awake”, I said. She said it hadn’t. I went back downstairs, found a hat to cover my unclean hair, which made me look more presentable than I felt. Again the bare minimum. I said goodbye to my wife, closed the front door behind me and stepped into the street.

The gallery is 10 minutes from my house. It is called The Launderette, a reference to the business that previously occupied the site. The Launderette is on Cheltenham Road, part of the long and meandering A48 that drops into Bristol by way of a long high street, which, confusingly, has different sections with different names: Gloucester Road, Cheltenham Road, Stokes Croft. Each section is full of independent shops, bars and food places, but there’s a distinct vibe shift as you move along it. From north to south, outskirts to centre, it goes from basic to bougie to hipster to edgy. It’s probably the street I have walked, cycled and driven the most since living here. There are record shops, restaurants, charity shops, vintage furniture outlets, board game cafes, hairdressers, galleries, and these shops and businesses manifest and reflect the the spirit of the road as it changes.

The Launderette is part of a parade of buildings that overlook a stretch of Cheltenham Road that is itself evolving. An old Victorian building that is now a mosque. The site of the old library houses a set of flats. The secondary school that was once Colston’s School For Girls has been renamed to become Montpelier School. Opposite The Launderette, to the left of a run of bars where young people spend their Friday and Saturday nights, drinking and dancing, is a Tesco Metro. The arrival of a Tesco Metro in this area just over a decade ago was the cause of a riot, a genuine and physical and occasionally violent stand-off between protesters and police. The resistance seems typical of this area of Bristol, though the form differs according to which stretch of the A48 you’re talking about. I suspect the residents of these different areas like to think of themselves as sharing an opposition to what the arrival of a Tesco Metro represents, the imposition of it, the unfair, top-down corrosion of the individual character of a place, a space colonised by commerce. People have told me that the part of the street that I live near, a section of Gloucester Road, has the highest density of independent shops in the country. There is a Costa Coffee, the familiarity of its deep red feels conspicuous there, and wrong. No one I know goes in it. That’s what resistance looks like at our stretch of the A48. It’s more assertive further south.

The exhibition at The Launderette was called Inadvertent. The website promised “16 painters responding to or in dialogue with the writing of Norwegian author, Karl Ove Knausgård.” I’d wanted to go from the moment I heard about it, having read a couple of Knausgård’s books and loved his writing. The book of his I couldn’t find that morning was one I bought on a family break a couple of years ago in Oslo, at the Munch museum. It was about Edvard Munch and Knausgård’s own emotional response to Munch’s art. I’d found the Munch collection inspiring, the beauty and the melancholy of it, the pain and the ordinary reality of the people he painted. Knausgård’s book, So Much Longing In So Little Space, sealed my experience inside the gallery the same way the photographs we took of the neighbouring library and the sauna on the edge of the Oslo fjord fixed in my memory the feeling of that whole holiday, the context and large emotions of the moment captured within a small and personal response to it. Experience contained in a small frame.

The book was my introduction to Knausgård and perhaps that was why I’d been searching for it that morning, as evidence of the affinity I felt with the author. Or maybe it was something less healthy. Did I want proof I was worthy of attending the event? Did I want to impress somebody - a person I didn’t even know - with the ‘cool’ option? The website had mentioned coffee, and an informal chat with the artists, also something about a book club, and perhaps I thought that if others were to bring books it was more likely they would bring something from the My Struggle series. Perhaps I might be the one to introduce to others his writing on Munch. Recognising the arrogance of this, or rather the insecurity which drove it, as I did in that moment, was the kind of over-thinking which on a bad day can have me chasing my own tail. On such days ambiguity and indecision can dominate, and the self-consciousness I attach to my own motivation swirls around with the delay tactics to which I fall prey. As it was, the point was moot, as I couldn’t find the book, and with a certain relief I noted that my hangover seemed to be pragmatic rather than existential, so I decided it was best to allow whatever was going to happen to unfold as it would.

Things felt lighter after that.

I walked at the pace I could manage, and told myself that arriving at the event at all was a win.

Besides, I thought, I didn’t need to justify my admiration for Knausgård, even if it was based on just a monograph and the first instalment of his monumental autofiction. When I finally read it, I’d been surprised to find A Death In The Family as compelling as I did. Critics use words like ‘unflinching’ and ‘excruciating’ to describe Knausgård’s description of the events of his own life. He goes into endless detail, avoids plot and doesn’t spare the feelings of the people he writes about, who are mostly his own family and friends. That kind of writerly entitlement put me off reading him for a long time - not to mention that he became an international literary sensation when my children were small, the time of life least conducive to reading long, plotless books about the difficulty of family, inheritance, failure and struggle. But I found Karl Ove’s world intimate and meaningful, addictive almost. He talks about the big stuff - death, love, family, work - but dwells mainly on the minutiae of what happened, and how he felt about it. His experience of life is right there on the page. His anxiety and his selfishness, his urges and his reactions. You do feel awkward at times, on his behalf and of those he writes about, but he writes with such fluency and directness that you can’t not keep reading. The anticipation builds continually, yet goes nowhere, until it arrives somewhere totally unexpected, the writing seems to ebb and flow like life itself, with long descriptions of apparently inconsequential moments that swerve unexpectedly into bursts of poetic epiphany.

On one occasion, Knausgård describes a moment outside his new office in Stockholm. As an immigrant from Norway, it’s a part of the city that’s unfamiliar to him, and he spends a few pages observing the shifting patterns of the day, the movement of people, marking the transfer of energies. He reflects on responses to his latest book and his struggles writing the new one. A novel needs a story, a friend says. Yet Knausgård feels there’s something meaningful in what he’s doing right now. No action, no intentions. Just the simple act of noticing and recording life as it unfolds in front of him. He writes:

“The sounds here were new and unfamiliar to me, the same was true of the rhythm in which they surfaced, but I would soon get used to them, to such an extent that they would fade into the background again. You know too little and it doesn’t exist. You know too much and it doesn’t exist. Writing is drawing the essence of what we know out of the shadows. That is what writing is about. Not what happens there, not what actions are played out there, but the there itself. There, that is writing’s location and aim. But how to get there?”

The idea that this might be the aim of writing felt thrilling to me. That this, hard as it was, was all a writer might choose to do, that it warranted spending a lifetime on, was worth risking the confidences of your relationships or the sanctity of your own inner life for, that bringing the essence of ‘there’ from the shadows was enough. This notion of writing, counter to the ‘write what you know’ cliche, makes an asset of unfamiliarity, and turns noticing into a responsibility. Intimacy comes from noticing at a distance. The practice connects us to the world, our relationship to it, our feelings, ourselves. It imbues even the routine, automatic stuff of life with magic.

Knausgård is a writer who sees. Of course painters would like him.

I stepped from the street towards the door of The Launderette and a woman smiled and invited me inside. Her name was Catherine and she was one of the curators. A small group of people were inside the gallery, talking. In the window at the front, just inside the door, was a small table, on it were a collection of catalogues for sale, along with a guest book for the thoughts and reflections of anyone who visited and an A4 print-out with the details of all the paintings in the exhibition. There were also two books by Knausgård. One of them, of course, was So Much Longing In So Little Space. I felt vindicated that the book I’d felt I should bring was here on display, a kind of totem for the event. Some of my anxiety fall away. The book’s presence and familiarity afforded me the sense of belonging I’d hoped for. But I also winced. It seemed arrogant and preposterous now to have imagined no one involved in an exhibition such as this wouldn’t have known about the book. I picked it up. “Have you read it?” asked Catherine. I said I had, explaining briefly about Oslo, the family holiday, the Munch museum. Catherine said she’d read it before ever going to Norway. Reading the book had inspired her to visit Munch’s world, to experience the surrounding landscape, to try to understand what might have inspired such art.

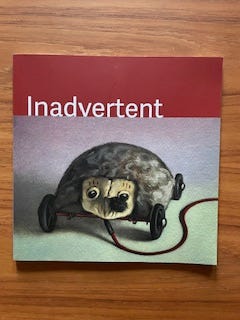

I picked up the other book on the table. It was called Inadvertent, the same title as the exhibition. Catherine explained the book was Knausgård’s contribution to the ‘Why I Write’ series. I flicked through it. I didn’t know such a book existed, and filed it in my mind as one to look out for. Catherine said she took the title because the philosophy Knausgård describes in the book captured well the techniques and approach many painters use. There’s a passage, Catherine said, where Knausgård uses the metaphor of hedgehogs in his back garden to explain an artist’s choice. You can either sit in the dark and wait for the hedgehogs to reveal themselves to you, he says, or you can walk around the garden and stumble across them. This ‘inadvertent’ approach was what Catherine and her fellow curator Andrew wanted to explore. Some artists provided paintings focused on ‘inadvertent’ subjects. One by Peter Jones featured a toy hedgehog on wheels, a child’s pull-along. Jones discovers his subjects on walks or pottering around unfamiliar places. Catherine and Andrew had chosen the hedgehog painting as the cover for the exhibition catalogue.

Catherine told me how the exhibition had come together. She and Andrew had the idea a few years back, and used Instagram to suggest the theme to fellow artists. Energy and momentum built from there. For a moment I felt something I hadn’t felt for a long time, a kind of positivity toward the internet, a sense of its possibility. Of late the internet had become something to resist, a malign force which stole my attention, time and focus if I let it, a means of reinforcing anxieties and separating people from each other. Catherine’s use of Instagram, turning an idea into the exhibition in which I now stood, felt like a throwback to a time when the internet could be a force for good, a gathering point for what we once called ‘communities of interest’, a way to forge relationships and galvanise them into something new.

I asked Catherine how active she’d had to be in her curating role. In other words, did most of the works already exist, or had artists responded to the theme as they would to a commission? I also asked whether all the work was directly and consciously inspired by Knausgård, or whether the curators had imposed a Knausgård connection based on their ideas of him. She said it was a blend of all of these, and talked a little about some examples of each. She pointed out work by Reed Wilson, a painter who had gone to art college and then not painted for twenty years. “I didn’t think what I had to say was particularly important,” she says in the catalogue, “and kept stopping.” Then one day she read the first book in the My Struggle series. “Something clicked and I stopped caring about what I ‘should’ paint. I decided to paint the light on a sweet wrapper, after that some paper bags, and I just kept painting. I never plan ahead and what I choose to paint is fairly random. I will have seen some beauty in an object at that moment, and want to capture it.”

I thought how sad it was to not express yourself for twenty years because of internalised ideas of what was worthy of your attention and your art. I thought how easily one day can turn into a week, into a month, into a year, then a decade or two, all of time passing until it all feels too big to even start. I thought too how powerful Knausgård’s big idea is, how transformative it can be on people who feel stuck, or those who get it.

In the catalogue essay, Catherine had included excerpts of Knausgård’s writing to add further meaning to the work in the exhibition. “When I first started writing, I was incredibly self-conscious and self-critical. I somehow published five novels, but then had five years of not being able to write. I had a set of pages that were just beginnings, beginnings, beginnings. With My Struggle, I learned to lower the threshold; to accept whatever comes; to continue and not throw away anything; and to do it every day.”

Catherine left me to look around the exhibition.

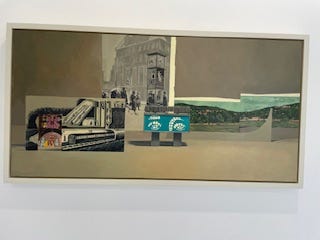

She handed me one of the A4 print-outs so I could follow the works in the order they were hung. Two by the same artist were the first to grab me, both collage. One was called Commuters. It featured a sideways elevation of an underground railway station, so that the otherwise subterranean movements of the passengers walking through the station were revealed to the world, and shown to be part of a system gouged out of a mountain-side. The everyday turned into something weird, remarkable, but also clinical and mechanic. Also in the collage was an image of an urban clock tower, which reminded me of Crouch End in North London, the Broadway, where people would queue for buses in a manner I never saw anywhere else in the capital, and next to that two images of a rural hillside. I couldn’t tell if the shape that sat in front of the images was paper, or something else overlaid on the painting, but it curved up sharply at the far right-hand side so that it reminded me of a ski jump, and I recalled the jump you can see on the hills outside Oslo from its bustling city streets in a certain part of town, the anomalous nature of it, the countryside and all its space viewed from the confines of centuries-old streets, the signs of winter viewed as they were from spring.

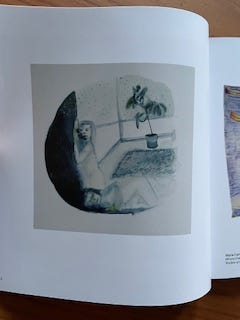

The next work I stopped in front of was called Where the voices come from and it made me think of Wedgwood pottery, a ghostly pale blue against ivory, figures who were both there and not there. Two people, perhaps children, were listening intently to the wall of their room. They seemed crammed into one corner of it. In contrast, a tall houseplant lay in the open of the room, next to a corner window, a vista to the outside world. What were they listening for, these ghosts? I immediately thought of the Dusty Springfield song, I Don’t Want To Hear It Anymore, written by Randy Newman. In the song Dusty is a woman pained by the conversations her neighbours have about her and the male partner she lives with, which she overhears through the wall of their apartment. “‘He don’t really love her’, that’s what I heard them say”. The male partner is cheating on her. I believe Dusty’s charatcer already knew this, but it’s possible this is how she found out. Either way, she would rather shut out the sound than confront reality. “The talk is so loud, and the walls are much too thin”, she laments, a ghost in her own life.

I wondered what the figures in the painting were hearing, whether they were confused or upset by the experience, or excited.

As I walked around the exhibition, Catherine approached me again and asked whether I’d like a coffee. A cafetiere, two thirds full, sat on the skirting board that ran around the gallery. “I would love a coffee”, I greedily replied. Something about the intonation, the candid admission of a need, left a space for others to fill, and a lady did, saying she’d noticed me looking at a painting which was hers. Her name was Maria Carvallo and she was the artist who made Where the voices come from. The figures were her children, she said. The work was created during lockdown, when the whole family was navigating that strange moment of containment. Maria herself felt ambivalent about the relatively recent role she’d taken on, that of mother, and carer, which is very different to being an artist. She had read Knausgård around this time, too. Maria said the children could hear voices from next door through the walls, though there had been a time when neighbours had complained about the noises they made. We talked a little about the contradictions of that time, about getting away from life while also making work from it, and the added dimension of being an immigrant. n that moment, the retreat of home was also a place of conflict and scrutiny, and judgement. I told Maria about the song by Dusty Springfield, but I suddenly couldn’t remember the lyrics. I implied that the relationship in the song is abusive, whereas the neighbours’ talk is only about the partner’s open infidelity. Nevertheless, it is a sad, sophisticated song, about a very particular domestic feeling, one more naturally the subject of art than a pop song.

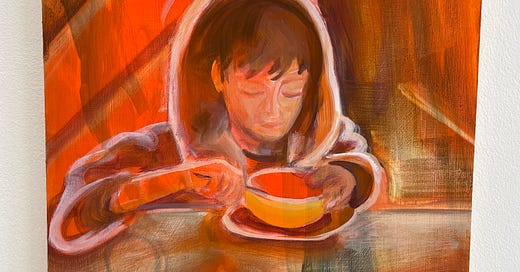

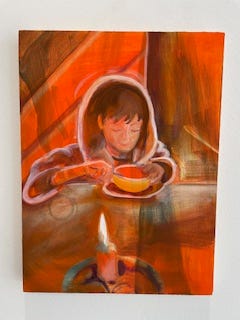

The works were hung in a circle, so that by the end I returned to the table by the front window that was laden with catalogues and the two Knausgård books. Along the way I realised how much depth can be captured within small squares of paint, the emotions art can evoke when it intentionally zooms in on all small aspects of life, or tries to capture feelings that are fleeting, but powerful. These moments get away from us unless art lingers on them. I felt filled with minor-key observations of life, and of the importance of capturing them. I loved the work that rendered scenes familiar from my own life, like Catherine’s own vibrant painting of her son eating a grapefruit, or Brendan Lancaster’s enigmatic portrait of his willowy teenage son posing distractedly in front of a mirror.

Tingling with the sense of connection, and with the hunch that sometimes precedes a piece of writing, a feeling I wanted to capture, or at least try to, I told Catherine that I write, and about the passage in A Death In The Family that meant so much to me. I tried to find it on my phone, scrolling for a few seconds too long for the moment.

On leaving the exhibition I decided to walk a longer way home, to take in more of the bustle and the day. The world seemed to burst with small frames and moments. The walk as Cheltenham Road became Stokes Croft was a riot of noticing. The street art and the graffiti, the fly posters, ripped and faded, promoting clubs and events, the blue sky that was almost as neon as adverts for raves, the queue outside The Crafty Egg cafe, snapshots of conversations as I floated past people. All of them potential subjects for yet more small squares of paint. How rich life is, I thought.

One fly poster was promoting a weekend of events dedicated to the radical history of Bristol, co-located at the Watershed, the M-Shed and The Cube. The Cube is a cinema that calls itself a ‘microplex’ and shows art films and theatrical performances you can watch on seats that when I went were old and uncomfortable and narrow, making it the opposite of today’s cosseted movie experience. I was minutes from The Cube and decided to turn off Stokes Croft along Jamaica Street. When I got there it was closed. I was too early for the day’s events. I decided to go and sit in King Square and flick through the catalogue.

The king for whom King Square was first laid out in the 1750s was George II. Today it is a communal garden that slopes up from Jamaica Street, but despite the grass and the open space you wouldn’t let a child come in here on their own. Its grandeur long since faded, it feels like a forgotten space.

The ideal seat would be the one in the top right corner, which a group of men were already occupying. With their backs to the rosebed border and their view of the square clear as it fell away from them clear, they were kings of the square for the day. Bottles were already open. One man occasionally did push-ups to show off his strength. Associates came and went. None of them spoke to the other man sitting down the slope, his bike propped against a bin. He would sit perfectly still for a few minutes before switching into an agitated jogging of his knee, the familiar blend of patience and alertness. I sat down on a weathered, wrought iron bench with chipped black paint and a wooden slat missing about halfway up the slope and looked around.

Tree branches swayed slowly in the light May breeze. Blossom fell, lit by the bright sunlight and falling on the grass like confetti at a wedding. The municipal bin next to my bench was uncovered, its square sides tagged and faded, but the bin bag inside was tightly tied, freshly fitted. The rose bushes seemed contained and cared for. As I settled into noticing my surroundings, the air was filled with a choir of birds, sprightly birdsong descending from the trees, seagull barks from overheard, the occasional caw. There was music coming from somewhere, too, a radio, I thought. A woman who sat further up from me, in her sixties or perhaps younger, smiling beatifically and wearing a thick coat far too warm for the weather, left her bench and swayed down the path carrying an apparently empty suitcase and a Waitrose carrier bag and tapping something into her smartphone. She walked towards me and asked if I was English. I said I was. As she got closer I could see the hairs sprouting from her chin. She pointed at the casters on the bottom of the suitcase and asked me what they were called. I told her, and after typing in the word she showed me the text to check she’d spelled it correctly. She was typing a text to tell someone about the the suitcase she had acquired. “You will like it”, it said. I asked the woman where she was from and she said “Bulgaria. I live here twenty years but I do not know every word.” She laughed and walked off smiling, continuing to tap at her phone.

Narrow roads bordered King Square on every side. Lining the roads were buildings that told the architectural history of the city, above the square were the old Georgian town houses, mostly now offices, the one at the end of the terrace was a car mechanic’s workshop, and I wondered if that was where the music was coming from. To the left and right the streets were cobbled, the car tires bobbling as they drove past. On the left the houses smaller and younger than the Georgian buildings, and residential, with Saturday morning activity happening as normal. A couple loaded their car, someone else arrived home with shopping. The wrought iron railings which must have once bordered the whole area still ran along the front of these houses, and over one hung a tireless bicycle wheel. It looked like a metal urban wreath.

On the right-hand side the buildings were more modern. Social housing, it seemed, and a community centre. Behind that and looming over the whole scene were the tower blocks that separate Kingsdown from Jamaica Street. I finished writing in my notebook and pulled from my bag the Knausgård book I had been able to find earlier that morning. A Man In Love, the second instalment of My Struggle. After reading a few pages I packed everything back into my bag and walked up the slope through the falling blossom towards the Georgian houses. As I crossed Dove Street to continue up the steep steps of Spring Hill, the apparently quiet moment seemed filled with life. The smell of fresh tarmac, still shiny and black on Dove Street, caused me to worry the tarmac might stick to my shoes, while I tried to remember whether this street had still been cobbles the last time I was here. Was I witness to a recent act of brutal modernisation, or had that ship sailed long ago? I had no memory of it either way. Ahead of me, two men, more alert than patient, were in the final movements of a drug exchange. They walked off in opposite directions. The music I’d heard while sat in King Square was louder now, and I realised it was a band, death metal, musicians playing at a furious speed and a man singing in a deep guttural growl as the music seeped out into the spring air from vents in the wall of the Georgian townhouse. They must have been playing in the basement all this time, their creative endeavour leaking out into the world while they remained hidden from view. I turned to go, but felt the urge to look one last time at the at again at the place I’d briefly made my own, a small square of fleeting interactions and transient feelings.