I can't stop thinking about Lankum...

A band that summons ghosts. Theirs is traditional music made for this moment.

I can’t stop thinking about Lankum…

I can’t stop thinking about the noise they make, the beauty and the terror of it, a sound at the same time intimate and enormous, unfathomable yet instantly familiar, mined as it is from depthless seams of sorrow and pain and regret, of death and love and class, so that words like ‘sing’ and ‘play’ seem too slight to describe what they do, instead the music feels summoned or conjured...

Even the horses keep watch.

I can’t stop picturing the four of them in a line, sat down and still, impassive from this distance, and I wonder whether they feel assured or awed, on a human level I mean, since it must be strange to go from small dives to 3000 capacity venues, but their sound expands as it fills the room, as they squeeze and turn and strike and strum, all while dwarfed by the largest drum you’ve ever seen, they are in total control, their songs vast and slow yet always in motion, the same chords over and over, turning like iron through earth...

Gaze to the left like their riders.

Who just wait.

Some fold their arms.

Some rest their hands on the horn of the saddle.

Watch.

Visors lifted.

Better to see what’s coming.

I can’t stop imagining myself within the eternal cycles of these songs, these murder ballads and suicide fugues, these lullabies and laments, the shanties and the reels, how it feels to be held by their melodies and chords and arrangements, structures that seem to hang in the air, that move from soft to fearful, or sad to jaunty, from acapella to overwhelming drone, usually over the course of six or eight or sometimes ten minutes, leaving you breathless, leaving you room to think, leaving you wondering how these songs survived, how they evolved over generations and even centuries, how they work…

Eight of them.

Men with wives and kids.

Men with orders.

Men with the force of the state behind them.

Paid to do its bidding.

For now they wait.

Stand together.

An island in a sea of wheat.

A tide rising to meet them.

Wheat brushing the underside of the horses' bellies.

I can’t stop sensing the ghosts reaching out from the past, some elemental disquiet scratching at the edges of the song, at times subsuming it completely, as if the protagonists of the songs come back to life, or the forces of their time are pulling them back, traversing distance and time and land to lay claim to their quarry, the disquiet grabbing hold of the music, sometimes suddenly and sometimes slowly and often irrevocably, so that it feels like a shift in the weather or illness blooming darkly against pale skin, tragic and inevitable, like Hades recalling Persephone, like the earth is forcibly calling in its debt, and it’s there as the mood turns and a dark pulse throws the music in Master Crowley’s off-centre, and it leaps from the momentary silence halfway through The New York Trader, plunging the song into the full terror of its ocean-crossing swirl, and when the music does this it’s like the inhabitants of these songs are held hostage by their own terrain, are swallowed by the undertow of life, the threat of it hanging in the air like the black smoke that billows over Lankum’s stage…

Wheat like Van Gogh’s.

Pointing in all directions at once.

Defying the orderly ideal of the countryside.

Resisting the arbitrary rules placed on it.

“What can a person do when he thinks of all the things he cannot understand, but look at the fields of wheat”, he wrote.

Nature.

An unmanageable sea.

The wheat cresting in spikes.

Betraying the lies of our imposed cycles.

Ploughing. Sowing. Harvesting.

All just attempts to control nature.

Enclose it.

Suppress it.

But wheat is life.

Eternal.

Van Gogh: “What the germinating force is in a grain of wheat, love is in us."

The scythe is death.

“We who live by bread, are we not ourselves like wheat... to be reaped when we are ripe."

I can’t stop shivering at the thought of Go Dig My Grave, which surges and soars towards it final form, a sweeping, searing noise that cycles round forever, drowning out the final testament of a woman whose parents find her hanging from a rope, the noise a siren of bewilderment and dread and grief, as if this tragedy stands for all tragedies, or augurs more to come, calls out its warning like a coastal bonfire, a beacon to protect a community blighted by madness, doomed to this life, claimed by the ground as part of some terrible destiny, and all the while a quiet, devestating image lies at its heart, at the woman’s breast, an image almost buried by the searing noise just as it is by the shovelled earth, a snow white dove which the dead woman wants placed on her chest, to “tell this world that I died for love”, making it a message of betrayal and forgiveness that will haunt the future…

The men on horses wait.

In a field in Orgreave.

Mid-June.

Harvest a month away.

The field ready for reaping.

Somewhere a machine roars into life.

I can’t stop smiling at the band’s warmth and wit, their easy camaraderie with the audience, the humanity emanating from the stage, Lankum being a group of people you want to spend time with, who want to spend time with people, who tell their troubadour tales of the last time they were here, of hanging out with the denizens of the Bearpit, a local Bristol landmark, a Glastonbury glade fashioned in Brutalist city-centre grey, a Ballardian fever dream come to life, a sunken roundabout with don’t-look vibes, where Lankum nevertheless went to drink and play till the early hours, because they walk it like they talk it, because all you can do in life is meet people where you find them and hear their songs and stories and their cries of protest, which they even find room to do on stage, bringing their hydraulic sound to an emergency stop just as it’s cranking upwards through the gears, as a frightened voice pierces the moment, makes itself heard over the rising spirit of history, a woman shouting, someone has fainted, and the group don’t even think about it, they instinctively ask if everything’s OK, and they ask again later, because ultimately they have a duty of care to the people gathered in here, because it’s not always easy to feel safe in a crowd, because things can happen, and besides some people are just more vulnerable than others, the social contract you live by is to look after them…

Rows bent over.

Backs and legs and hips all put to work.

Flat caps.

Donkey jackets.

Boots.

Hoes scrape.

Hammers tap.

So nothing goes to waste.

They keep going.

Not potatoes.

Coal.

Farming for warmth.

Imagine that.

In 1984.

What choice do they have.

How else to heat their homes.

The homes of others.

The homes of everyone who relies on them.

You can wiithdraw your labour but you must still work.

Ask any woman in the village.

Ask the kids.

Always been that way.

No different now.

There are obligations.

So the harvest goes where it’s needed.

Gets shared out later.

It’s what you do.

What you owe each other.

What THEY don’t seem to understand.

Not socialism.

Not necessarily.

Just community.

Survival.

Love.

It’s instinctive.

Buried deep.

Old as the hills.

Firm as the ground you stand on.

I can’t stop reflecting on the cosmic symmetry of my week, the Lankum gig on Thursday and a visit two days later to the Martin Parr Foundation, to an exhibition commemorating the 40th anniversary of the miners’ strike, memorobilia alongside the photography, a blend of documentary and folk art, rescuing a violent, noisy moment from the resting quiet of history, a reminder of a story of a community in crisis, a community coming together, testimony of another world, of an existential threat, of a year of struggle that must have felt like a lifetime, ordinary people forced to do extraordinary things, the extreme becoming simply part of life, the everyday brutality, the toxic tribalism, the violence barely contained within gestures, an absent authority now the enemy, a trauma buried and calling out to us years later…

A gulf.

Inches wide.

Two sides miles apart.

Too much said.

The left is a crowd.

The right is a line.

The crowd is a seething mass of competing impulses.

The line doesn’t move.

The crowd surges forward.

The crowd holds itself back.

The line doesn’t move.

The crowd does both at the same time.

Too many men to speak as one.

Swirling waters in a choppy sea.

The line doesn’t move.

The line has a job to do.

Thankless work.

Dangerous work.

The crowd has a job to do too.

The crowd has mouths to feed.

The crowd doesn’t know what it is if the pit goes.

The crowd has honour to uphold and on its side.

The crowd feels powerless.

Scared.

Stripped of dignity.

The line doesn’t move.

I can’t stop wondering where history goes while it’s waiting for us, before someone plays a song or shows us a photograph, when history becomes invisible to those who wish it, until everyone forgets it ever was and it’s left to explain the silences and absences of our lives, the things that aren’t said, the people who go away, the opportunities that never come...

It never gets less shocking.

This moment before the moment.

The outreached arm.

The swing.

The pace.

Her raised left hand.

Futile.

Brutal treatment.

Brutal logic:

The miners resist.

The miners are the enemy.

Their supporters are the enemy.

Solidarity is taking sides is support.

Women Against Pit Closures.

Means: women for miners.

Means: women against police.

Means: women against law and order.

Means: women who are wrong.

Women who must be fought.

Must be told.

Must be shown.

What happens when this happens.

When the state turns on its people.

When the state says some deserve less than others.

Says: you’re either with us or against us. Says: against us is wrong.

There’s no map for this. No history lessons in school. No answers at the back for the unanswerable questions that follow.

Who protects you? Who defends your home? Do you belong here? Where would you go?

Big questions.

From tiny words.

Communities exploded by single syllables.

Coal.

Work.

Strike.

Pig.

War.

Scab.

Especially scab.

So mean in the mouth.

The onomatopoeia of it. Nasty, brutish and short.

The life of man? Solitary and poor.

The lives of desperate men. The lives of women forced to make a choice. Children with none. The inexorable logic of war. Miner against miner. Family against family. Where does it end.

Here:

In this bungalow.

Smashed. Roof collapsed. Firebomb thrown.

Slate and brick broken. Beams ripped apart.

A home turned inside out. A community turned on itself.

Supporting structures gone.

A family within. They can’t live here anymore. Can’t live anywhere.

People doing terrible things. Deeds they regret. Words they can’t take back.

Bury it. Can’t go back. Something lost forever. Betrayal and resentment the new birthrights. Do our best to forget it. Forget who caused it. They’re not here. They don’t care. They’re all the same. They destroyed communities. People’s livelihoods. Their prospects. The bonds between them. The ties that make society work. All collateral damage.

Standard of living: down.

Whole areas: empty.

High streets: hollowed out.

Gaps and decay and infection and rot.

A cartography of bad dentistry.

A layer of society left behind.

Nowhere for the pain to go. Push it down. Push to forget. Carry it. Let it mutate and infect and spread. Let it find a new target. They’re all the same. It will come out somehow. It will tell you it wants to Leave. That will show them. Show THEM.

But it won’t end the betrayal. The bitterness. The sense of a community crippled. No work. Trust gone. Authority corrupted. Deaths and endless tragedy and fights.

The sort of thing they write folk songs about.

I can’t stop circling around the band’s name, Lankum, which was taken from an old ballad called False Lankum, which is also the title they gave to their new album, but beforehand was just a song known colloquially as ‘Lamkin’, more officially as Child Ballad no 93, and which was captured for posterity on a field recording by an Irish Traveller called John Reilly Jr, so that Lankum’s name is itself the process of folk culture, a mangling of sources, of tradition and mutations, of whispers and interpretations, of story and teller, a conversation between reference points and mishearings, between words and ideas that evolve from something else, an accretion over time of new meaning, because words change and don’t Lankum know it, having adopted the name to replace their original name, Lynched, which had worked because Lynch is the name of the two brothers in the band, and which in modern Irish parlance means to be jumped on by a gang, but whose connotations of racist violence the group felt they could no longer ignore, and so they changed it, because keeping the past alive is not the same as identifying with it, and sometimes to commemorate history you must break with it, theirs being a traditional music played for the present, for today’s audience, and for those still imprisoned within a history they didn’t choose, and they made this as clear as they possibly can, saying when they made the change that “we will continue to stand in firm solidarity with oppressed, marginalized and displaced people, both here in Ireland and internationally”, which is why their traditional music feels so alive, because history is not fixed, is not its statues or its monuments or the stories of its victors, but is rather the testimony of the people who lived it, and there is always more of that to hear, always more history happening, even now, especially now, always more to understand, always more to pour into a community’s art and stories…

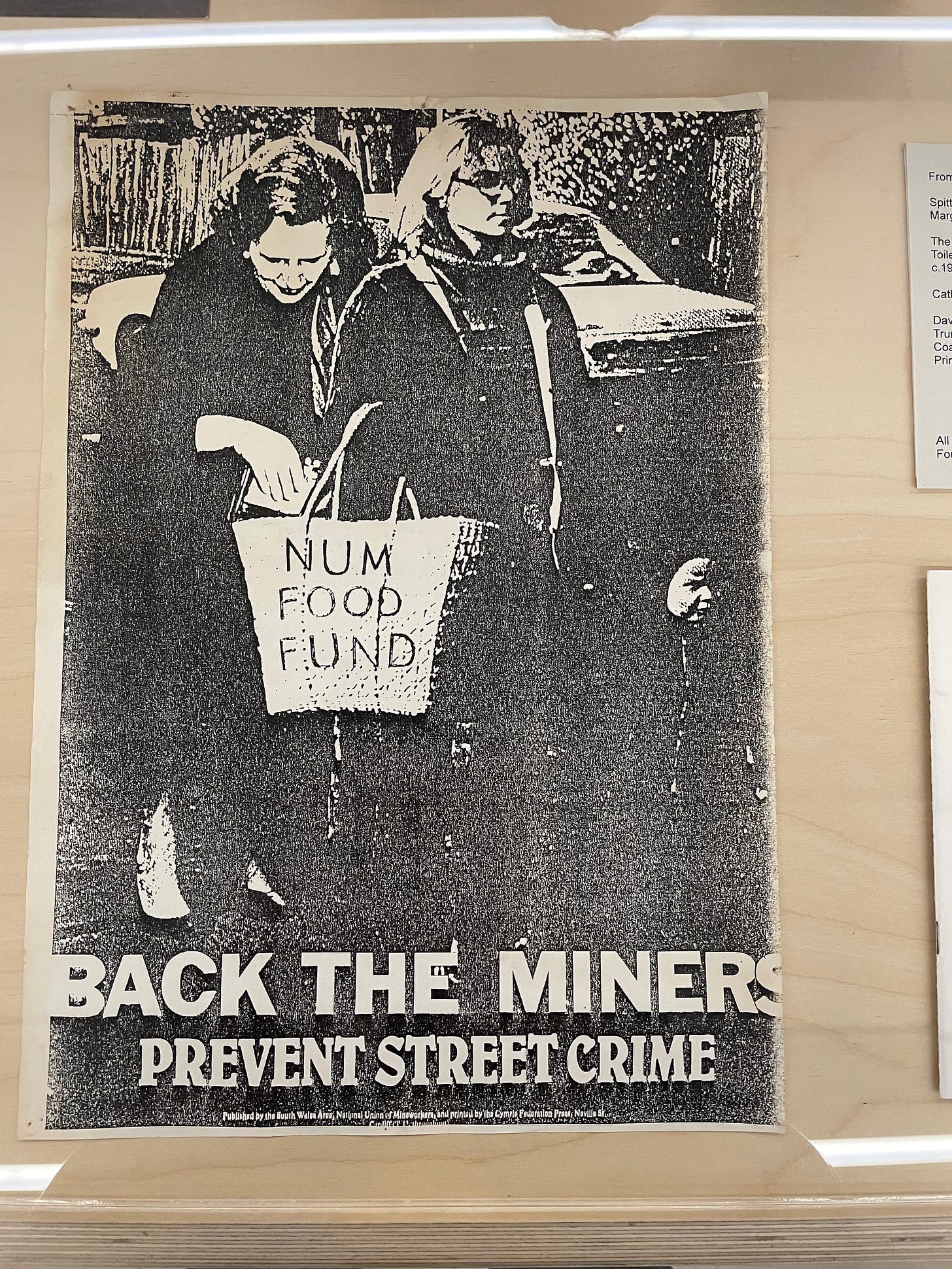

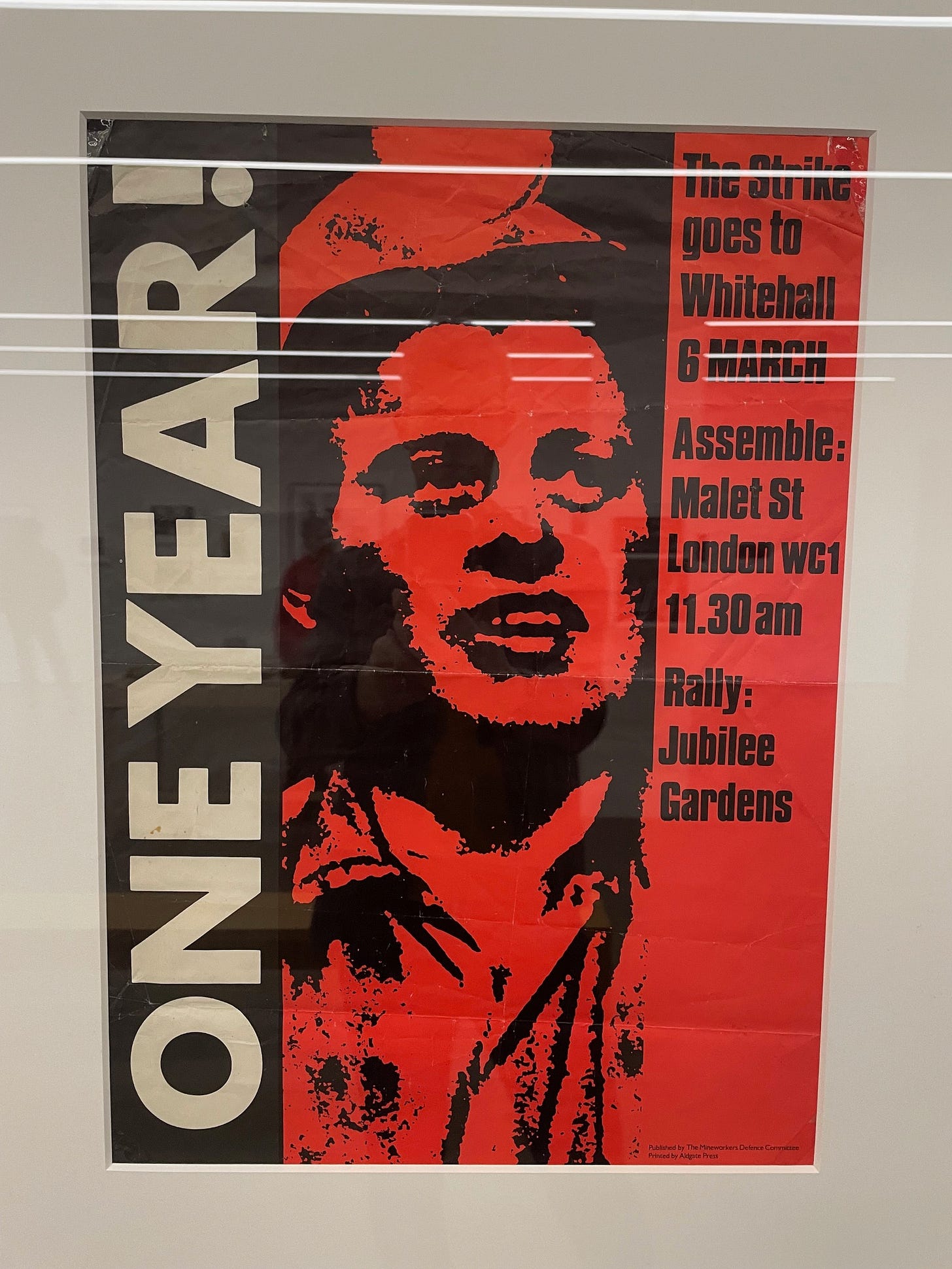

The humanity.

It shines through.

Humour.

Creativity.

Resourcefulness.

Collection boxes and commemorative plates.

Posters that poke fun and placards.

Signs and rugs.

Folk art.

Transmissions from the past.

Messages from beyond the grave.

Symbols to haunt us in the future.

Depictions of reality. Calls for help. Cries of protest.

This isn’t politics.

It’s culture.

Life in 3D.

A way to build morale with jokes.

A way to promote attendance at events.

A way to offer help.

A way to fundraise.

A way to vent frustration.

It’s what people have always done.

Think: pirate radio.

Think: tea towels and songs and tapestries and Chartism.

Think: punk fanzines and message boards and blogs.

Think: ‘Votes For Women’ scratched on an old penny.

Think: ‘under the paving stones the beach’.

Do it yourself. Tell your own stories. Make your own spaces.

Ideas. Dissent circulating. Demands promulgated. Bonds manifested. Strengthened.

Images and ideas and stories depict the culture that made them.

Then they travel through time and space to tell us what happened.

To tell us what it meant.

To attest to what it was like.

So we hear the story less told.

So we see the love.

I can’t stop thinking about something Lankum do tonight, barely missing a beat when someone in the crowd shouts “free Palestine”, and they respond instinctively and warmly, saying “either ‘never again’ means ‘never again for all’ or it means nothing at all”, saying it should go without saying, a formulation that tells you where they stand, this group that sings of criminal men and murdered women, of betrayal and displacement, of curdled authority and human tragedy, they sing of pain and suffering, of real people, their lives, their stories, their right to be whoever they are, wherever they are, and they are prepared to say so from the stage, even though it costs them, even though they’ve had gigs cancelled in Germany for expressing pro-Palenstinian statements, even though many would rather look away...

Sometimes history won’t leave you alone.

Sometimes it demands you take sides.

You’re the enemy within. An interloper. Born in occupied territory. Unwelcome.

Because of who you are.

The life you inherited is worth less than others.

Some let this happen. The ones in charge. The ones who demonise and diminish and pretend that it’s all normal. Who break communities that don’t serve them and sow division because that does. Who rule by force. By occupation. By removing people’s means to a livelihood. By making citizenship contingent. By running down industries. By privatising public utilities. By selling housing stock so it tithes working people to credit not unions. They are the mendacious ones. Who feign interest in ordinary people for their electoral value. Who speak reasonably and say what needs to be said but never what they mean. Who trade lives for power and call it common sense.

But then there are the others. The people who don’t see all this. Who even vote for it. Who internalise lies and reject humanity. Who blame the miners. Who blame the immigrants. Who blame the refugees. Who blame whoever the other is. Who think something needs to be done. Who are glad someone’s saying it. Who wouldn’t agree with the language used but would broadly back the sentiment. Who think the ends justify the means. Who fall for some golden age myth. Who turn away from the stories and the images and the cries and the tears and the pain and the horror and the grief because it’s all too hard to take. Who wring their hands in retrospect but sit on them at the time. Who are blind now to what is later obvious to all: that the fight is rarely with the people they say it is. The fight is with the people who tell you there’s a fight.

We are human. We are weak. We fail. We forget. We take sides. We choose not to see. Choose not to hear. That’s why we need art. Art that is testimony. Art that gives power to ordinary people. Art that places a frame around the lives we cannot live. Tells the stories that otherwise disappear. Art like that is louder than fear because it lets its subjects tell their own story. Art like that is photography. Is folk music. Is authentic. Is unmediated. It travels from a history buried deep underground. It traverses distance and time and land to grab us by the throat. It is a snow white dove covered with earth yet still able to move us to tears. It is a community that wins with love in a game made for them to lose. It is moments of regret and connection and fear and solidarity all captured for posterity. For us to see. So that when the world spins out of control, when the worst happens, the people to whom it’s happening can tell the rest of us. Can pass it down the generations.

Our only job is to hear them.

One Year! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-5 is on at the Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol until 31st March, 2024. More information here.

A BBC documentary commemorating the strike’s 40th anniversary is here. Channel 4 have also made a series which is here. For fictional accounts, try David Peace’s novel, GB84, which is excellent, or Sherwood, on iplayer here.

This is my introduction to Lankum, so bloody hell James.

I watched the BBC documentary and was left feeling bereft for (most of) them. This captures it all perfectly

"Scab.

Especially scab.

So mean in the mouth.

The onomatopoeia of it. Nasty, brutish and short.

The life of man? Solitary and poor."

Your essays are getting better and better; richer and more profound. You know I'm a fan, but a discering one. Keep it up :)