Now that we're all Friends

How a 1968 Beach Boys album shows us how we live now. Self-care & over-sharing, mindfulness & working-from-home - in songs made for short attention spans.

All Brian can say is he likes it here.

He never likes to think too much, but the positive feeling he has among the trees, looking out over the garden, is obvious. It’s the calm. He can sit quietly, long as he wants. No one is used to his living there yet. He hears birdsong, sees the sun dapple the soft grass. It gives him peace.

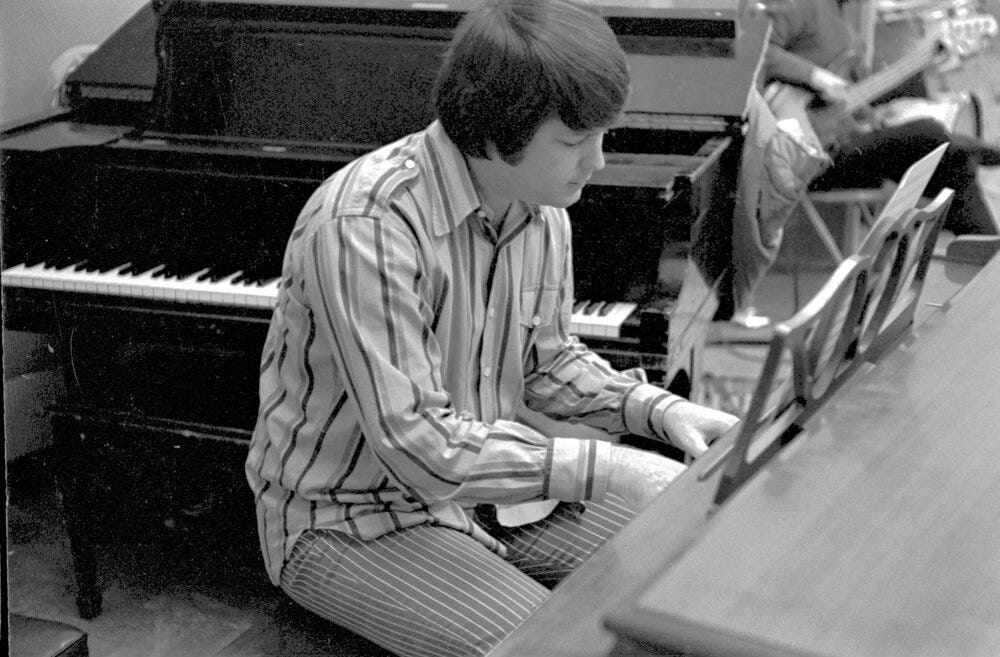

Sometimes more than that. There are times he’s in his favourite room - this one, with the piano - and the boys aren’t touring so he can use the equipment, he’ll be playing as light falls on those white floor tiles, warmth of the sun against the coolness of the stone, and the stained glass splits the light into multi-coloured pools of water. A psychedelic floor. Like a kids’ kaleidoscope. The colours come apart and make new patterns just like the music does in his head. Then the harmonies come to him from the wind in the trees, gathering underneath him in swirling eddies of light. Moments like that he thinks the house is perfect.

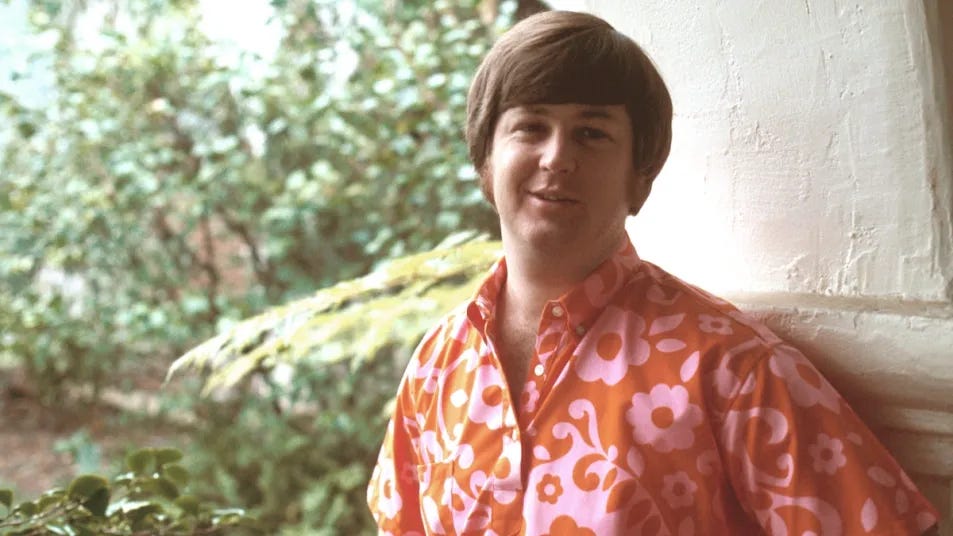

Six months ago he left the old place - hoo boy did it all go crazy back there. But 10452 Bellagio Road is good for him. He’s meditating. They all are, after India. The boys are happier, even Mike. No grand concepts this time around. Just music that feels good. Songs Marilyn and the baby will like. He’s already hearing arrangements. Walking through them, like the drooping willow branches that line his lawn. Melodies are coming the way they do sometimes, from outside. What are melodies really but the play of light and air.

He moves his hands on the piano, waiting for the moment the lines are lovely enough to catch the sun and dance in the multi-coloured pools at his feet. He knows he wants a record that sounds like that. That feels like that. Like a kids’ kaleidoscope. Like a calm Bel Air day.

By early ‘68, it was no longer clear what the Beach Boys were for.

Too weird for pop, too straight for the hippies, they were in limbo. The avant-garde’s hopes for Smile disintegrated, as did the scene’s optimism, a darker, more serious ‘rock’ mentality emerging to replace it. The Beatles sang about revolution. The Stones sounded like it, channeled Bulgakov to make global heroes of street-fighting youth. Everywhere the sound of charging feet; here and there the sight of necks on the line. Mick Jagger outside the US Embassy in London, James Brown stopping riots in Boston. The story that stuck was that the Beach Boys lost their nerve at Monterey. Fearing arrest for draft-avoidance, they pulled out. No one else cared and all offered more. Hendrix was noisier. The Beatles more important. The Stones sexier. The Byrds druggier. Love weirder. The Doors more dangerous. The Beach Boys trailed a Pacific Coast mile behind ‘em all - psychedelic psuburbanites losing ground to the city kids.

A year before, the Beach Boys were pioneers. No one else did sound better. No one else was Brian Wilson. Pet Sounds, Good Vibrations and Heroes And Villains were - are - at the outer limits of what pop music can do. Their music was a warm cocoon, a way to hold its listeners within a feeling. In his mind his records actively transmitted love - that most essential idea of the 60s - and their arrangements, their very contours and textures, were engineered to embody and conduct sensation. There’s little more psychedelic than that. But by ‘68 the cracks were showing. Brian was ill-suited to fame and pop’s relentless pace. Acid, anxiety and burn-out did for him. He abandoned Smile. The group fought to recover and feed the machine. Unbelievably, Smiley Smile and Wild Honey were both released in the second half of 1967. All too believably, both were underwhelming. The world moved on.

The group stayed in limbo. From this limbo state came Friends.

From a passing glance, little had changed. Even by post-Smile standards Friends was thin. It ran for 25 minutes, each one indifferent to the turmoil of 1968. Political unrest, riots and war were nowhere, held at bay by the secure walls of Brian’s garden. The group assumed no one was listening. The group was correct; like its predecessors, the record sank. It is mostly ignored even now. Certainly it is few people’s favourite Beach Boys album, with none of the critical acclaim of the records that came after. Even in 2020, in a Quietus feature celebrating those later records, listening to these limbo albums was described as "panning for gold, elbow-deep in shit."

Yet Friends deserves better, and it’s worth getting up close to see why. Brian Wilson was pleased with it, later describing it as his “second unofficial solo album” (after Pet Sounds) because he produced it, making it more coherent than its predecessors. Paradoxically, Friends also marks the moment this family finally became a collective entity. While no one was listening, the atmosphere of Friends kickstarted that journey to critical rehabilitation - it’s the first Beach Boys album to give writing credits to all three Wilson brothers, and in the privacy of Bellagio Road there flourished something supportive and experimental, work mode that drew fresh, original contributions from all members, the kind you hear more of on Sunflower, Surf’s Up and Holland.

But Friends deserves better because what made Friends too small to meet the moment in 1968 is precisely what makes it so relevant to ours. In its subject matter and the manner of its making, Friends is driven by impulses that reverberate today: notions of mental health, hybrid work, mindfulness. It captures what it means to recuperate. The urge to notice. The instinct to tether your perspective to a tangible reality and nurture valuable relationships. “Let’s be friends”, runs the title track’s mantra, and it’s really an album about connection. What made connection a tangible reality within the walls of Brian’s garden that Spring was the acceptance the Beach Boys showed to one another, and to the world, and for once even to Brian, who just wanted to stay home. Pop was no stranger to volatile personalities or drug-induced breakdowns in 1968, but the familial duty of care shown by the group to Brian was new, and not only to them. Sure, bands had recorded remotely before (‘getting it together in the country’ already had the whiff of corporate away-day about it back then), but the Beach Boys did ‘work from home’ first. Ensconced in the Bel Air foothills on Bellagio Road, theirs was a mode of recording that would flourish in the 80s, with home studios a convenient if costly solution for rich and famous musicians trying to balance comfort with creative freedom. The Beach Boys did this to accommodate Brian’s mental health challenges. To prioritise self-care and psychological safety. To achieve it, they prototyped a remote-working solution. Friends is pop’s first ‘safe-space’ album.

The preoccupations of its songs follow. They are small, recuperative, and prescient. The hippy ideals and Bulgakovian leanings of the Beach Boys’ peers ring hollow in 2024: youth voices are more likely to demand we check our privilege than change the world. But the benign solipsism of Friends resonates. Meaning is found in beauty: sunsets, bird song; and in mundanity. The doors of perception are opened not by mild-altering hallucinogens but by meditation and mindfulness. The Beach Boys wrote Friends in grain-of-sand close-up; listeners expecting grand statements and philosophical inquiry must have winced. But its short songs betray a skittish attention span and an impulse to share even the most inconsequential experiences that are instantly familiar to us. Friends is self-absorbed, trivial, and easily distracted. It is the first album of the social media age, made 40 years before Facebook.

Not that Friends inspired anyone directly. But contemporary digital life is a deluge of dull information, a gushing river of mundanity. We might see in Friends the headwaters of that river. None of this mattered to Brian. In 1968, he had lost his nerve and was soon to lose his mind. He was in retreat and only just in charge of the Beach Boys. For the first time, he needed them more than they needed him. For the first time in a long time, he got a creative process that was also a source of comfort.

At the start, it’s more a family gathering than work.

Later, as songs take shape and the Wrecking Crew arrive, there’ll be the cadence of a proper recording schedule. But for now they sit playing in the spring sunshine, writing, the boys in Brian’s home, ten miles and a world away from Capitol Records. Eating, hanging out. Jokes and memories flung around. Get stuck, they go sit on the dappled lawn. LA life is easy again, warm, the winter chill endured for another year.

There are tensions. This is family, after all. But silence is quickly filled by birdsong, the soft swoosh of the California breeze jangling the leaves of the trees. It used to feel like a battle for control over writing credits, the music, the very idea of the Beach Boys. Today Brian can see how invested they all are. They’re meeting each other again. For the first time. As adults. In return, he tries not to dominate. The big decisions are still his to make. He still composes uncredited sections for the boys’ songs, in the same way a host might offer more food to his guests. He doesn’t want widescreen vistas or teenage drama. All the inspiration Brian needs is right here, in the music encoded in the world: the elegant calm of water, the billowing promise of air, the feeling of doing nothing.

Dennis has a line: Brian doesn’t write music, he transcribes it.

Family is full of contradictions, Brian thinks. The strongest love, most quietly expressed. It’s here Brian feels most sure of the love that supports him, yet of all anywhere he goes, he is least likely to hear the words said out loud here. Thinking is hard, he thinks. For now, he relishes everything turning inward: the family, the music, the songs. They’ve made this small and intimate circle, and it’s Brian job to shrinkwrap it in sound. From that softly psychedelic room comes music that is intimate, warm, rich in colour.

Music that is centred.

Smile did emerge in the end. At least, excerpts did, on those early 70s records. Much like Brian himself by then, they showed up in spliced and reconstituted form. His music gives the records an uncanny air. The experience is akin to a Christopher Nolan film that flits between two competing timelines - the group racing forward to meet Brian’s example, while Brian’s vision haunts them from the past. Accompanied by memories of their resident but ailing genius - their own (benign) Spector-at-the-feast - the rest of the group felt able to use his music as their real-life brother disintegrated in real-time. As the stitches and seams of Brian’s psyche came apart, somehow his brothers, his cousin, and a series of floating collaborators embroidered the threads of increasingly diverse solo work into something coherent and unique - a beguiling, cosmic Americana tapestry.

Friends contains no such musical CGI. All Beach Boys occupy the same moment. Being in the here-and-now was kind of the point: Friends is the sound of a family turning its collective attention inward, a group finding its centre, thanks to Transcendental Meditation. TM was big news in the late 60s, counter-cultural and spiritual. The Beatles’ went to India to learn it, and returned with the stirrings of The White Album. Others went deeper still. The Mahavishnu Orchestra made an album inspired by TM called The Inner Mounting Flame. Its songs had titles like Meeting of the Spirits, Awakening, and A Lotus On Irish Streams. The cover included a poem by guru Sri Chinmoy. Mike Love returned from India with a song about Mike Love visiting his favourite masseuse. (Anna Lee, The Healer opens side 2 of Friends). It is very Beach Boys, to be so nearly at the countercultural cutting-edge, but not quite.

After the headfuck of recent years (and, I suspect, trauma caused by the Wilsons’ bullying father), meditative practice brought calm to the group’s world. Friends might not reflect or inspire true enlightenment but it shines with the infectious enthusiasm of the convert. The conversion was to noticing - an engagement with ordinary, day-to-day living. The cycle of days. The imminent birth of a child. A momentary delight of nature. It is a record defined by fleeting moments of awareness, mini-epiphanies, the kind we all have when we pause and realise the quiet wonder of being alive, accept the small things as the big things. Brian fashioned idiosyncratic arrangements for these observations. Tracks meander, then dart about, as if taken with passing thoughts or capturing Brian’s naive delight in things, his appreciation of life.

Meditation is supposed to quieten the mind. It demands, and then allows, the practitioner to simply be. Many claim profound change can come from its practice. For the Beach Boys - this pop group that was also family, members thanks to circumstance as much as choice - it meant letting go of baggage that had coloured their relationships and their work. It might have looked from the outside like disengagement with the volatility of the times, but within their walled garden the group was conducting a quiet revolution of its own. Perhaps on some level they were preparing. Over the next few years, Brian’s influence and the certainty it brought would wane. He was to drift further from reality and from them. Perhaps the sense of togetherness they forged at Bellagio Road was the signal his psyche needed: that it was safe to disconnect. That there would be a place to come back to.

In crisis, the group grew. They began finding a new identity. As individuals, they found some inner peace. Collectively, they were learning to become themselves.

He paints with sound. Conjures moods with strokes. No daubs or smears. Ears are delicate. The music’s textures should reflect what he hears. What the boys want to get across.

Meant For You he’s pleased with. It has to open the record. It’s the feeling of giving way to meditation. Letting go. Mike sings differently. Softer. “As I sit and close my eyes, there’s peace in my mind, and I’m hoping that you find it too.” Brian puts a church organ underneath - a long, soft note. A forever ‘om’. A piano tinkles like a tree breeze. “This gift,” sings Mike, “is meant for you.” The thing lasts seconds. It’s a walk into his garden in the morning.

He sees the atmosphere at Bellagio Road as an instrument. An ambience or feeling he can dial up. Not that it’s always quiet. Sometimes a song calls for a riot of sound - the sound of a family at play, not fighting. Be Here In The Morning seems quiet and gentle, yet it’s full of kazoos and theatre organs. A small guitar caresses the right side of the sound, there’s a treated vocal fill, a Hawaii-style ukulele strums away too, all while the drums brush round in waltz time. He hides little discoveries for the listener, cute sounds that appear briefly then disappear. There’s the rousing brass and strings that seem to surge from nowhere on Dennis’ Little Bird, and the swelling organ that suddenly drops out as the song makes room for a sprightly excerpt of Child Is The Father Of The Man. Smuggling in a small bit of Smile. He uses the Wurlitzer a lot - it sounds like childhood to him, comforting and uncertain at the same time.

He loves getting to this level of detail, fixing the song’s meaning in the smallest of moments. He might push an instrument to the foreground if it captures the mood, like with that plucky, woody, rousing bass sound on Anna Lee, The Healer; or the church-like, beatific calm of the organ on Be Still. Sometimes it’s the song’s structure, like when Carl sings Wake The World. He sings about the stars appearing and disappearing at the start and the finish, so Brian lets the music fade in and out, the sense of a continuous cycle at either end. The chorus, in contrast, is a burst of joy at “the brand new morning.” He’s so proud of Diamond Head, named after the volcanic mountain in Honolulu. He wanted it pure - the sound and feeling of a day overlooking that place. It lilts, then it’s unsetting, and ultimately transcendent.

At times there’s no gap between their music and the world they’ve made for themselves. In meditation, he feels at one with the elements. He feels at one with the music. He feels safe.

Friends was too quirky, too small for 1968, but it makes sense today. Now we’re literate in the grammar of self-care. Now every laptop producer is a bedroom Brian Wilson.

In 2023, BBC 6Music broadcast a radio show of ‘homemade’ music. The theme was chosen to mark the 20th anniversary of Four Tet’s Rounds, a ‘folktronica’ record from 2003. The wistful and dreamlike music of Rounds, harp-strings swirling like tendrils around the slow crackle of shuffling beats, is nothing like that on Friends, but the two share an evolutionary biological history. Like Friends, Rounds sees life from the edge of a bustling city, and wonders at nature without seeking to tame it. Like Friends it was made by a young man deploying at home the available means of musical production. Listeners suggested the music for the radio show; no one chose anything from Friends. Home-recording is widespread and well-understood, but awareness of Friends is not, and it proved a very quiet kind of Big Bang - a flap of butterfly wings, its ultimate effect the result of innumerable serendipities. We might say it was an accidental turn onto a road that accumulated more traffic - avenue became highway became freeway, with home-studio landmarks such as Hounds Of Love and Lovesexy (the first Prince record to be fully recorded at Paisley Park) widening its lanes.

It’s a road that leads all the way to Rounds, and onwards still further, to a place on the horizon occupied by something like I Love You, Jennifer B by Jockstrap, released in 2022. (Their track, Concrete Over Water, appeared on the 6Music show.) Jockstrap were classically schooled at London’s Guildhall but chose the life of intuitive artists who also operate computer programmes. Their debut album is quirky, sonically inventive, and organically synthetic music generated by technology unimaginable to Brian Wilson in 1968 - music that exists in its own world. As a listening experience it is patchworky and distracted, a shifting tapestry of textures and genres, as if Jockstrap have inherited Brian Wilson’s attention span as well as his production nous.

The road that leads from Friends to I Love You, Jennifer B via Rounds is enabled by cheapening production technology. But it’s also the story of artists harnessing that technology to articulate their dislocation from the modern world, reflecting the increased use in the wider world of communication technology. It’s never been easier for bedroom Brian Wilsons to construct their own sonic world, and never easier for their audiences to feel apart and alone and connected by such music. What Brian felt in 1968 the modern world has extended, normalised and reinforced for all of us.

Music has evolved to reflect our state. In 2014, Lauren Laverne wrote an article claiming contemporary music sounded lonely. This “music of the laptop” was a product of accessible technology, of shared spaces that are disappearing, and of financial necessity. The “sound of [London] now is languid and nocturnal,” she wrote, “conjuring the hypnagogic state between waking and sleeping, occasionally becoming claustrophobic. It sounds isolated.” That year, Damon Albarn released an album in his own name. It was a “very personal record” dealing with themes of “nature versus technology.” Albarn brought in co-producer Richard Russell “to create a particular atmosphere and mood, it's quite an atmospheric record.” He called it Everyday Robots. The opening lyric called us “everyday robots on our phones”. Albarn, writer of London first as a dayglo parade of literary characters (Parklife) and then as a tableau of melancholy communal resilience (The Good, The Bad and The Queen), felt a record made about London in 2014 should sound “very lonely.”

Friends doesn’t sound lonely, but it does soundtrack a retreat, just as Paul McCartney’s first solo album did - the one he made at home on a farm in Scotland before the Beatles’ split was announced, a perfect blend of a ‘getting it together in the country’ record and a work-from-home one. McCartney played everything on McCartney himself. It was unpolished, intentionally rough. This was retreat as an exercise in self-reliance - proof to himself and the world he can do it on his own. He can start from scratch, make a doer-upper of his career like he did the farmhouse. It’s better known than Friends as the seminal ‘homemade’ album - not just for its DIY ethos, but as an advert for domestic quietude, for a softer kind of masculinity, even.

At the time, McCartney and the Beach Boys both stood accused of indulgence, of indifference to the world’s problems. Today, we accept the world’s noise and its effect on mental health is the problem. We recognise flight when we see it. In 1968, music demonstrated. It sought to instigate change or project ego. Now we want music that enables, that reflects our atomised reality, that encourages acceptance. Introverted music. We crave music as an intimate form of connection, now each of us walks around a figurative walled garden of our own making.

Friends makes more sense today, now that Friends is how we all live. Now that we’re all Friends. Its lyrics read like a scroll through a very familiar Facebook feed, the Live Laugh Love kind. New days and nature. The love letter to an unborn child (but really for everyone else to hear). The songs that evangelise about self-care treatments like musical Yelp reviews. The instrumental Diamond Head is an aural equivalent to an Instagram sunset shot. The title track is guileless as a Facebook poke in 2008. The inconsequentiality is part of the record’s charm, but like your Boomer relative, or old school friend, or the dull colleague you worked with in 2008, you’re left wondering what less forgiving audiences will make of what they write.

Friends is how we live now because our walled gardens are built from preoccupations and passing thoughts we choose to share with the world. The machine once fed by the Beach Boys with hastily released albums, now feeds us. That machine is near-sentient. It encourages us to nurture emotional connections it pretends to understand. It serves us the content and perspectives it knows we want, thanks to the things we tap and click. The promise of the internet was to connect everybody to the information of the world, but in many ways it reduced our field of vision. We’re drawn to the never-ending feed, and surrounded by - at the mercy of - the passing thoughts of anyone who takes the time to write them down. Mundane musings define our reality. It’s a world we’ve all made: each of us can retreat to a space to excavate and then release what’s in our minds. No Capitol Records contract required. No barrier between our thoughts and our ability to transcribe them for others.

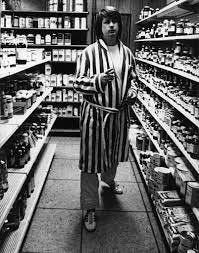

On Busy Doin' Nothin', a track towards the end of Friends (though the album is so short it feels like a centrepiece when it arrives), Brian Wilson literally writes what he’s thinking. He fills three minutes of easy-listening bossa nova with traffic directions to his new house and, in minute detail, his efforts to contact someone:

I wrote a number down, but I lost it so I searched through my pocket book, I couldn't find it so I sat and concentrated on the number and slowly it came to me, so I dialled it and I let it ring a few times, there was no answer so I let it ring a little more, still no answer, so I hung up the telephone, got some paper and sharpened up a pencil and wrote a letter to my friend.

It’s the longest vocal track on the album. That feels significant, though its lyric doesn’t. When my wife heard this song she laughed out loud. It is ridiculous. It doesn’t rhyme. It’s like listening to a child explain something in too much detail. But it bounces along, and is delightful, partly thanks to the way the melody resolves at the end, partly because it shows us Brian Wilson struggling with connection, trying his best. As the world burned, he founding his way through the fog the way we all do, sharing the monotony that gave him a sense of place and structure. Now that we’re all Friends, you can’t say we use our platform with any greater profundity than Brian Wilson managed. We whinge and complain. We dox and unbox. We share and review. We reduce the wonder and majesty of the planet to a picture of ourselves momentarily occupying a small part of it. (“Me in the museum of me’”, as Kae Tempest charged a few years back.) We each write our own version of Busy Doin’ Nothin’ everyday.

It’s said the history of the internet is the slow march towards things we said we’d never do - share our bank details or address, get into a car with a stranger, transgressions without which Uber would have no business model - but it is also the rather quicker march to us being interested in things in we thought we’d never be interested in, not least among them the mundane doings of other people. Such distractions have become essential - ‘everything’, in today’s inflation-fuelled review-speak. In this world, a celebrity doesn’t need product to remain in the public eye, they just need content - a peek behind the wall of their garden (figurative, literal, doesn’t matter) will do. Fifty-six years after Friends, there is money to be made listing and doing your day’s chores, while you wait for your siblings or a friend to arrive, or you deal with a work conflict, or row with your neighbours. You just need to be a Kardashian, or a real-estate salesperson, or a ‘real’ housewife. You just need a film crew to pretend they’re not there. You build an audience and their attention earns you money. This is so commonplace we barely question it. We are lured into the home lives of people who weren’t famous before we found them talking directly to us on video, each of them living out their lives, busy doing nothing. We love them for the way we think they live, at the most banal level, because of what they tell us to watch, or how to clean, or exercise, or what to cook, or how to play a game, and we subscribe so we don’t miss the latest instalment, just like they ask.

Friends is how we live now, because our own banality is a plea for connection. We’ve always craved this. Social media didn’t invent this impulse - just listen to Busy Doin’ Nothin’. Sharing something of ourselves is how we do it. Studies (like this one) show we share mundane things on social media if we feel uncertain or doubt ourselves, just like Brian did. Or we do it because we feel lonely at work or among our family, just like Brian did. We might want to share something even if not much is happening in our lives - or perhaps precisely because our lives are empty, since we might worry that people otherwise forget us. We might crave an anonymous audience, because it makes us braver, feel less exposed, more able to share something we wouldn’t say to a friend’s face. We might feel isolated, cut off from others, or not as liked as we once were, or hemmed in by an absence of social skills. We might not feel great about ourselves and so turn to the blue light that’s always there, because it asks nothing of us, though it takes plenty, and which sends us into the world less sure of who we are or what we want. We might find refuge in the minutiae of celebrities’ lives, the parts they let us see, at least, and imagine they are our friends.

We share our own monotony and enjoy the monotony of others because we are lonely. Or sad. Or suffering from low self-esteem. Or because we are self-centred and we struggle with adult ways. Perhaps all of these, as was likely the case with Brian Wilson, a man who built a sandpit under his piano so his feet could sit in sand while he played, who was physically bullied by his father and taken for granted by less gifted members of his band, who wrote and produced music savant-like in its complex beauty yet which embodied some kind of prelapsarian innocence, and who eventually found happiness for a while at the home where no one could find him or make demands of him, and experienced one last moment of lucidity and connection before the darkness swallowed him for more than a decade.

Now it’s finished, he reflects on a job well done. The songs make him feel safe the way he wanted. The warmth of a typical day at home. AThere are no bad vibes. If you’d told him a year ago that would happen, he wouldn't have believed it.

He loved it when they all sang “Let’s be friends” like that. He felt appreciated. From the looks on the boys’ faces, they all did too. No one had to say anything. That song also reflected the fun they had making the record. That’s why he made it a waltz, hung a whole toy-box of sounds around it. He had fun placing more instruments in the mix, making sure not to overpower the mood of the song. Playing Buckaroo with the studio. He thinks of those miniatures his mom used to show him. Precious portraits of her family, brought over the mountains when they crossed to California, kept safe over the generations. They were small paintings, rich in detail. Intimate. When he was a kid she would tell him their stories, tell him this was how people who loved each other stayed connected back when there was no other way. They were given as mementoes by departing loved ones, or as a symbol of courtship. They weren’t for display - the person they were given to carried them around. Kept them close.

That’s how he wants the people who listen to Friends to feel. It’s not showy like Smile. It doesn’t need to set the world alight - there’s enough of it up in flames as it is. What matters is the people who carry it with them feel the love Brian felt when he made it. That the people who matter now know what they mean to him. That listeners in the future know it too. He filled in all the details he could. Brought to life how the moment felt to them.

Brian’s thoughts carry him away. Will people listen to Friends in the future, he wonders? Will they carry it into their own dark places, the way he did, or to those new horizons, the way those first Californians did with their miniatures? Surely, Brian thinks, people will always want to hear songs about the important things. It’s so easy to forget the simple joy of being alive. The privilege of being here to witness everything nature has to show us.

And friends. Even decades from now, Brian thinks, we can all still be Friends.

This is really great Jim - I too like the linking to Four Tet and Jockstrap (an album I really enjoyed) and the opening couple of paras in particular are a joy - great work!

Loving all the strands and connections. Who's is the voice in italics? Adding Friends, Jockstrap to my listening list, and going to revisit Rounds. Wonderful x